New publication provides an introduction to Historical Cryptology

Worldwide libraries and archives are treasure troves of encrypted historical manuscripts, including diplomatic correspondences, intelligence reports, private communications, diaries, and texts linked to secretive circles. In the realm of Historical Cryptology, scholars and cryptologists are engaged in uncovering methods to decipher these encrypted sources. The methodologies and challenges involved in this pursuit are outlined in a chapter of a newly published book.

Beáta Megyesi is a professor of computational linguistics at the Department of Linguistics and the principal investigator of the DECRYPT project. It is an interdisciplinary research project with representatives from various fields needed to analyze ciphers: computational linguists, computer scientists, historians, historical linguists, image analysis experts, and cryptologists. Together with her colleagues in DECRYPT, Beáta has written the chapter "Historical Cryptology" in the recently published book Learning and Experiencing Cryptography with CrypTool and SageMath (Artech House, 2024). The chapter provides an introduction to analyzing historical ciphers, from collection and digitization to transcription and decryption. The process also includes interpretation and contextualization of the message within its historical context.

Challenging source material

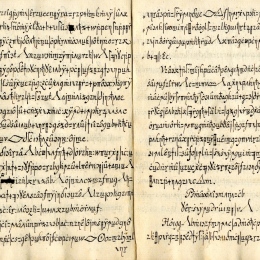

The manuscripts studied in Historical Cryptology are mostly handwritten sources.

– They exist in archives and libraries worldwide, but they are often hidden without any form of indexing, making them difficult to locate, Beáta Megyesi explains. Once found, they need to be digitized and converted into a machine-readable text format before they can be deciphered. She emphasizes that there are many difficulties when working with historical encrypted texts.

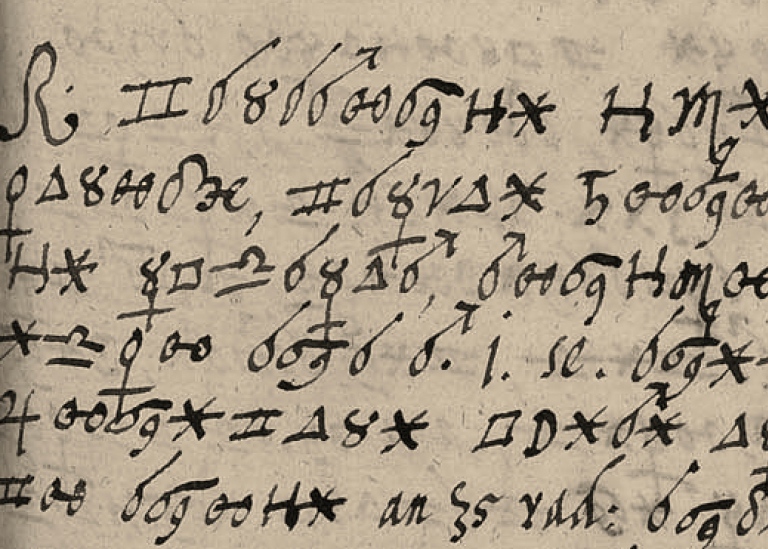

– Transcription is one of the biggest challenges as we need to convert the image into text format. It is time-consuming and often a source of errors. They consist of many different symbols and unusual writing systems; they can have difficult-to-read handwriting and the pages migth be damaged. And the underlying language uses old or outdated languages. Beáta also points out that encrypted texts vary widely in how they are coded, with different characters and symbols.

There is a large amount of material with rare or unknown writing systems from our history far back in time, waiting for analysis and decipherment.

– The most common encryption methods historically were to replace letters or characters according to certain principles where alphabetical characters, syllables, words, phrases, or sentences could have their own codes.

New research field

The research field of Historical Cryptology is new, and Beáta Megyesi believes there is much to explore.

– We need to gather more material to create better algorithms that can be used to assist with the transcription of different symbol systems, and we need better analysis methods adapted to historical variants of the world's thousands of languages.

So far, DECRYPT has only focused on European ciphers from the early modern period.

But there is a large amount of material with rare or unknown writing systems from our history far back in time, waiting for analysis and deciphering.

– And for that, we need robust tools to help historians, linguists, and researchers interpret these historical sources, says Beáta. Next on the agenda is the further development of our transcription tool, which will be integrated with the crypto-analysis tool so that they can be used together and released online.

Read the chapter on Historical Cryptology

Read more about Beáta Megyesi's research

Read more about the DECRYPT project

On the DECRYPT website, you will also find more ciphers and the tools developed within the project.

Last updated: February 29, 2024

Source: Department of Linguistics