Genes that separate woolly mammoths from elephants revealed

Scientists have managed to map far more DNA than anyone has ever done for an extinct Ice Age animal species. A new study identifies mutations that were unique to the woolly mammoth - which probably underlie the mammoth's hair growth, fat storage and small ears.

See the slide show at the bottom of the page with finds of mammoths in Siberia.

Researchers at the Centre for Palaeogenetics, a joint venture between Stockholm University and the Swedish Museum of Natural History, have conducted a ground-breaking study in which they analyzed the genome of 23 woolly mammoths. One of the individuals is one of the oldest known woolly mammoths that lived 700,000 years ago. The results, now published in the journal Current Biology, provide new insights into the evolutionary process and are an important step towards creating a comprehensive catalog of the genetic changes that underlie the woolly mammoth's unique appearance and physiology.

The woolly mammoth is an extinct species of elephant that lived during the latter part of the Pleistocene epoch, from about 700,000 years ago until its extinction 4,000 years ago. The species was adapted to live in a cold climate and had a thick, woolly fur, small ears and extensive fat deposits.

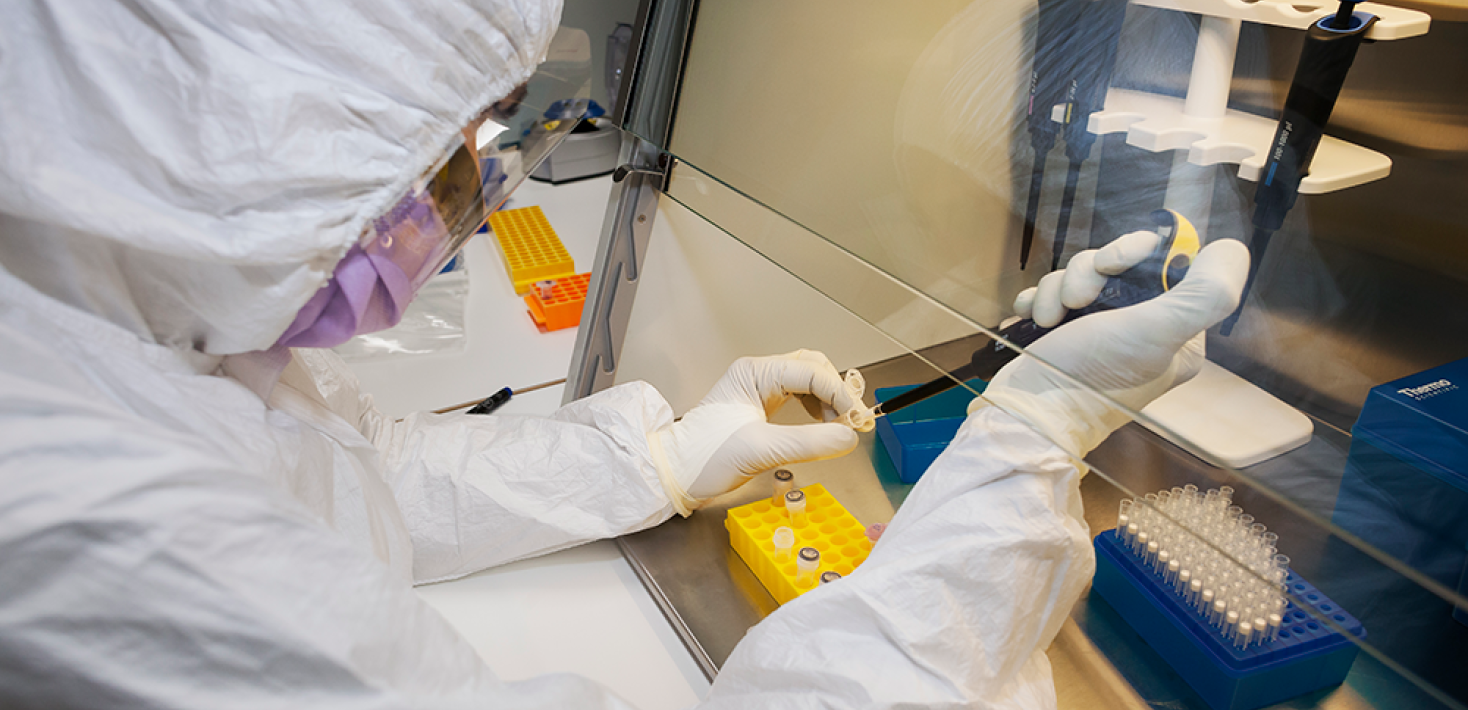

“By combining the latest techniques in palaeogenetics with large-scale sequencing, we have managed to map much more DNA than anyone has previously done for an extinct Ice Age animal”, says Marianne Dehasque at the Centre for Palaeogenetics and one of the article's co-authors. She recently defended her doctoral thesis at Stockholm University, which dealt with the genetics of the wollly mammoth.

Mutations unique to the mammoth

“Our analyzes have made it possible to identify mutations that are unique to the woolly mammoth and we have also been able to form a picture of when these mutations arose. The results show that even the very first woolly mammoths had several unique gene variants linked to hair growth, fat storage and the function of the immune system”, says Love Dalén, professor and researcher at the Centre for Palaeogenetics.

The researchers also discovered that some of the woolly mammoth's classic traits, such as its woolly coat, continued to evolve over the past 700,000 years, but that this happened through mutations in genes other than those previously selected by natural selection. In addition, the researchers found mutations in the mammoths that they hypothesize caused them to have smaller ears. These mutations occurred over the past 700,000 years.

“This type of analysis is unique and provides an important insight into how natural selection works”, says the study's first author David Diez-del-Molino, researcher at the Centre for Palaeogenetics.

Significant for the understanding of species adaptation

According to Tom van der Valk at the Centre for Palaeogenetics and who led the research together with Love Dalén, the results are significant for our understanding of how extinct organisms were adapted to their environment.

“By examining prehistoric genomes, we can learn more about the genes behind various adaptations, which in turn can help us understand the evolutionary processes that shaped the world we live in today”.

Article in Current Biology: Genomics of adaptive evolution in the woolly mammoth

Mammoths found in Siberia

Last updated: April 7, 2023

Source: Communications Office