Stockholm researchers one step closer to large satellite project

The European Space Agency ESA is set to select the next major satellite program. Researchers at Stockholm University are behind one of the four main candidates.

The European Space Agency's Earth Explorer program has over the years launched five research missions into space to provide important research data, and there are six more programs at various stages of development. In early 2023, the program issued its twelfth call for proposals. Seventeen applications were received, and recently ESA decided to allow four of these to proceed to the next stage of the process, where the program proposals will be scrutinized more closely. One of these research programs will be selected as ESA's twelfth Earth Explorer in 2029.

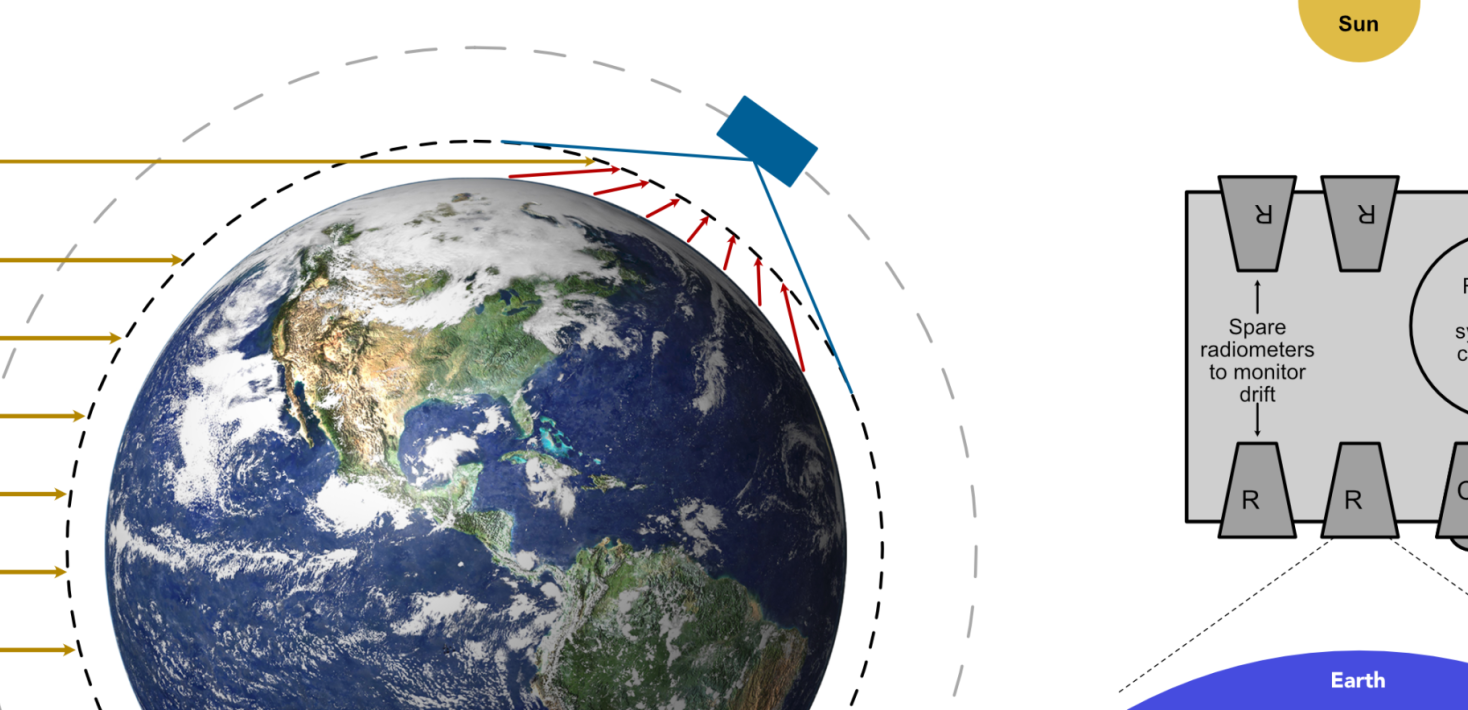

One of the four programs that ESA has selected for the second round is the Earth Climate Observatory (ECO), which aims to measure Earth's radiation balance. "We want to measure Earth's radiation balance directly from space. It is the relatively small difference between incoming solar radiation and reflection, plus infrared radiation from Earth. This is something that has not been achieved before," says Thorsten Mauritsen, associate professor at the Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, and one of the three researchers leading ECO.

Radiation balance key to understanding climate change

The radiation balance is key to understanding where climate change is heading. Imbalance arises due to increasing greenhouse gases, which in turn leads to heat accumulation in the atmosphere and oceans. Global warming, in turn, leads to heatwaves, extreme precipitation, drought, shifting climate zones, and rising sea levels.

When countries around the world are striving to keep Earth's global temperature increase below two degrees, it is crucial to have a system in space that can quickly and reliably indicate whether the measures have had the desired effect before it is reflected in temperature trends over the coming decades. One can also learn a great deal about how the climate system operates by having long, uninterrupted time series of radiation balance.

"As climate researchers, there is also a slight concern that our forecasts for the future may be completely off. The widespread belief among climate scientists, which I share, is that global warming will plateau at approximately the level of warming reached a few years or a decade after phasing out the use of fossil fuels. But even though the risk is extremely small, there are fears that feedback mechanisms could continue to exacerbate global warming afterward. Such a nightmare scenario could be detected early with ECO, and then there would be more time to react," says Thorsten Mauritsen.

Reducing uncertainty in measurements

He explains that current and planned American satellite systems have insufficient accuracy to measure the minute imbalance; instead, their focus is on high resolution.

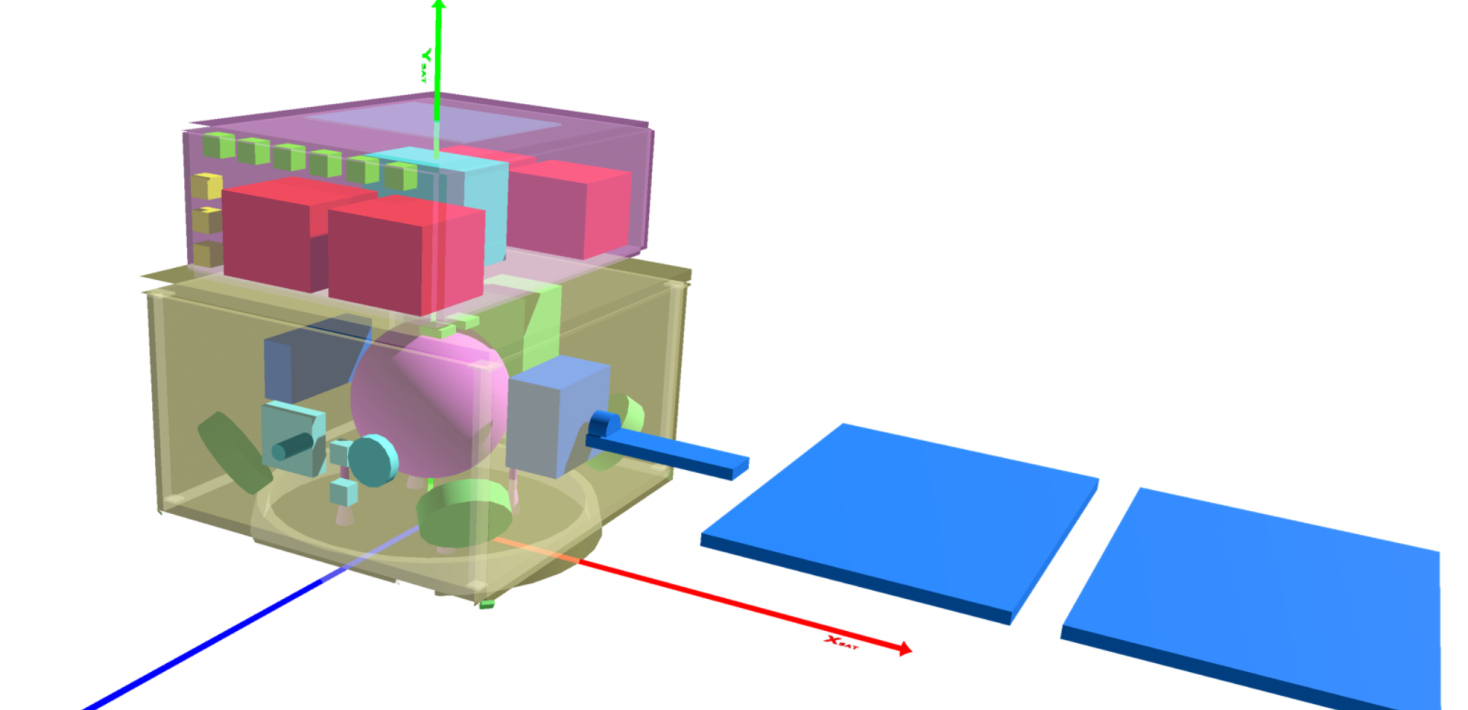

"In ECO, we plan to take a different approach to achieve our goal. We will use instruments that measure reflection and radiation from horizon to horizon from the satellite's perspective, as well as identical instruments to measure solar radiation. We also have a duplicate set of instruments. This way, we can reduce uncertainty and achieve very stable measurements over time, even if the harsh space environment wears on the instruments," says Thorsten Mauritsen.

Measurements day and night all over the Earth

To measure radiation balance, measurements need to be taken day and night, and everywhere on Earth. Stockholm University researchers have shown that this can be achieved with at least two satellites in specific orbits over or near the poles.

"These orbits are so cleverly oriented that at different times of the year, measurements are taken at different times of the day. The more common approach is to use sun-synchronous orbits where measurements are always taken at the same times of day, usually around noon and midnight. However, the diurnal cycle in radiation balance is immense, so if such orbits were used, at least six functioning satellites would be needed, which would be very costly," says Thorsten Mauritsen.

Tough selection process

Until 2029, there will be a tough selection process to determine the mission ESA will choose. During this time, researchers within ECO will conduct a series of tests to ensure the system will work. ESA will also investigate whether European companies can build the satellites as intended and if any modifications are needed. After 2029, the satellites will be constructed, with the launch planned for 2036.

What do you hope to achieve with ECO?

"We hope to demonstrate the value of monitoring global warming from space and that the ECO mission will be followed up so that future generations can better monitor the climate," says Thorsten Mauritsen.

Researchers from six countries behind the application

In addition to Stockholm University, researchers from Brussels and Toulouse are the lead applicants for ECO. Stockholm University researchers also include Linda Megner and Jörg Gumbel, both from the Department of Meteorology, in the application, and much of the research has been carried out by doctoral student Thomas Hocking. In total, twelve researchers from Sweden, Belgium, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland are behind the application. The budget framework from ESA for the project is 550 million euros. In the current stage, the four programs are allocated a smaller sum, primarily for industry studies on how the mission could be realized.

The other projects moving forward are CryoRad, Hydroterra+, and Keystone.

Last updated: April 29, 2024

Source: MISU