Fewer herring in the Gulf of Bothnia

The Baltic herring stock in the Gulf of Bothnia has fallen to critical levels. It is said that the herring have become smaller and is not growing as it should. But above all, it is the number of herring that has decreased – by more than 50 percent over the past decade. The largest decrease is among older individuals.

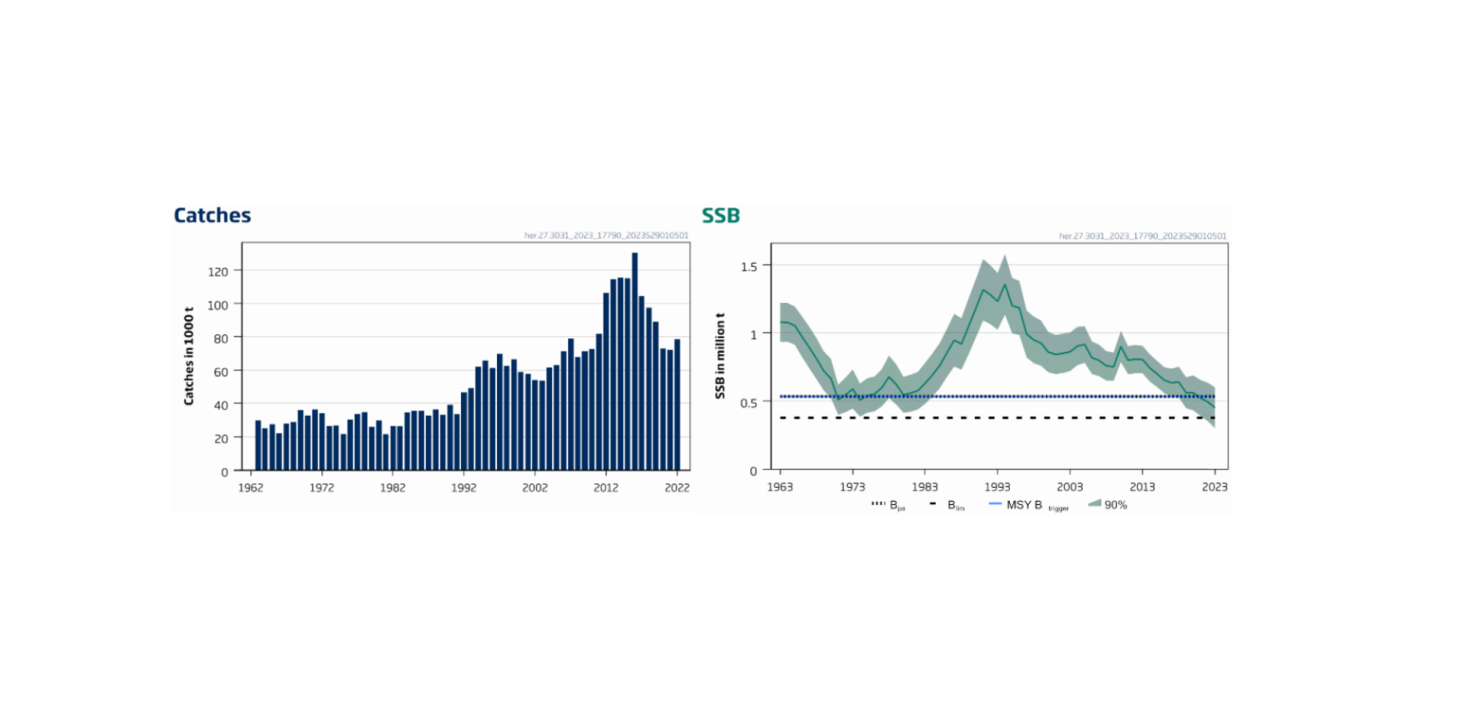

There is no doubt that the Baltic herring stock in the Gulf of Bothnia is in trouble. The spawning stock biomass has declined sharply over the past decade and is now at the limit value Blim, when the stock is at risk of collapse.

Spawning biomass indicates the amount of mature fish in the stock, and is measured in weight. The weight of the spawning stock biomass is governed by two things: the number of mature fish in the stock and the weight of the individual fish. 2,000 spawning half-kilos fish make up the same spawning biomass as 200 five-kilos fish.

The question for the Bothnian herring stock is whether the sharp decline in the spawning stock biomass is due to the fact that the herring have become smaller – or that they have become fewer.

ICES highlights weight

Local coastal fishermen and fermented herring producers in the Gulf of Bothnia have long warned about a shortage of herring in general and of large herring in particular. They believe that the large-scale industrial pelagic trawling has depleted the stock by catching far too many herring in the open sea before it enters the coast to spawn.

However, among those managing the fisheries, a somewhat different analysis is carried out.

"It's strange that the herring doesn't grow as it did before, and that we don't have such big herrings anymore," said Swedish Minister for Rural Affairs Peter Kullgren (KD) to SVT News Gävleborg ahead of the quota negotiations in the EU Council of Ministers a few weeks ago.

The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) also emphasizes the problem of weight and growth in its advice for next year's fisheries. According to ICES, the decline in spawning stock biomass in recent years is "in particular" linked to a loss of weight among the older herring in the stock:

“It is likely that this downward revision in SSB is related to the downward revision of recruitment and stock numbers in 2021–2022 and (in particular) the lower body condition of the older herring. The reasons for the decline in weight-at-age are not understood and it is partially accounted for in the forecast.”

Plummeted in weight – 20 years ago

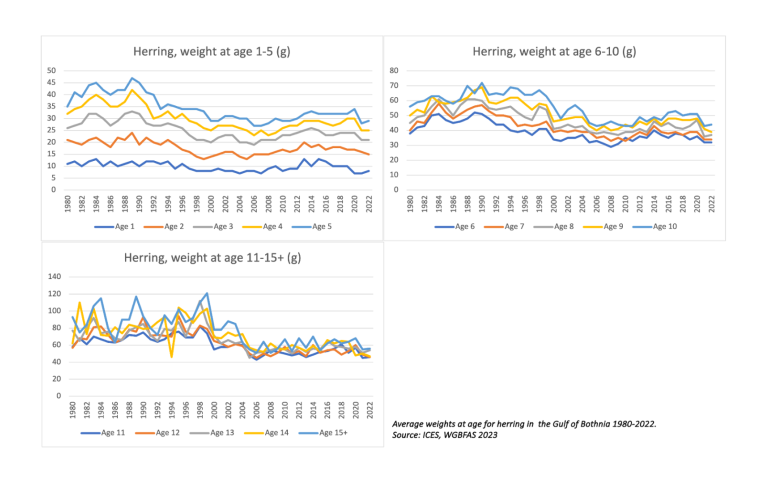

It is true that the Bothnian herring has lost average individual weight – but the big decrease occurred about 20 years ago.

In the early 2000s, the average weight of the older fish in the stock plummeted. Between 2004 and 2005, herring aged ten years or older lost up to 20 grams in average weight. A probable reason was that the crustacean white marl (Monoporeia affinis), which is an important food for Baltic herring, was severely decimated in the Bothnian Sea during the same period. After a few years, however, the average weights stabilized and have remained relatively constant ever since.

Between 2020 and 2021, the average weight decreased quite sharply again in most age groups, and remained at that level in 2022. Prior to that, however, the average weights had been increasing for several years. Compared to the average weights of Bothnian herring in 2010, the differences from the average weights recorded in 2022 are relatively small – one or two grams – in most year classes.

The number of herrings has halved

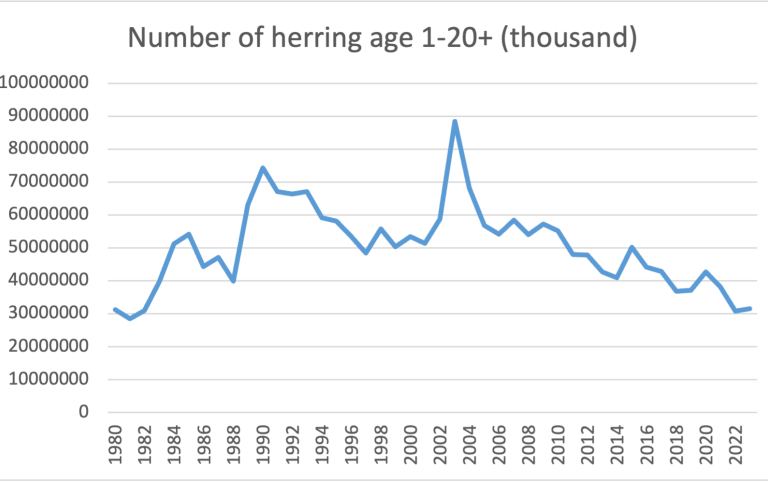

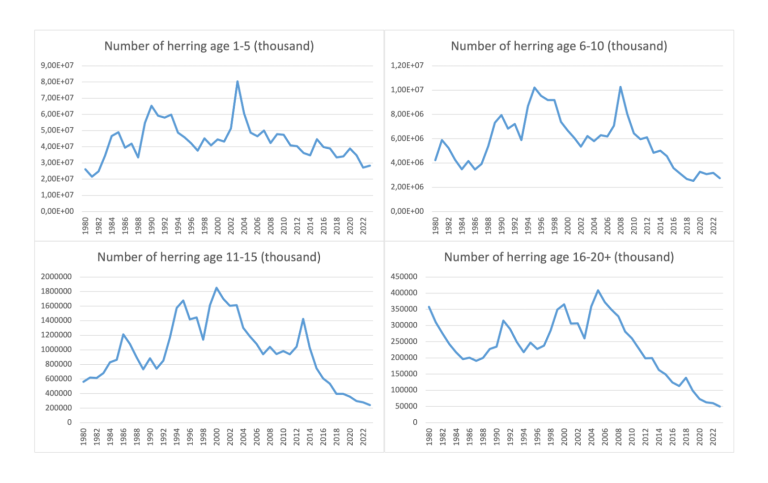

However, something that is not emphasized in ICES advice is that the number of herring in the Gulf of Bothnia stock has decreased very sharply over the past decade or so. According to data in ICES stock assessments, the number of fish aged 1 to 20+ in the stock has halved from around 60 billion individuals to today's 31 billion individuals.

The largest decline is seen among older (and larger) herring, aged six and older. The number of really old herring, 16 years and older, has decreased by about 80 percent, from 260 million individuals (2010) to about 50 million individuals today.

During the same period, the number of 11- to 15-year-old herring was decimated by 76 percent, from about 1 billion to just over 240 million. The number of 6- to 10-year-olds decreased by 60 percent and the number of 1- to 5-year-olds by 40 percent.

Over the past decade, the number of fish have declined sharply while the individual weights of the fish have been relatively stable. Yet, ICES emphasize the average weight in its latest quota advice.

"In the advice ICES only refers to the last few years, since 2020. However, I can agree that the phrase 'in particular' makes it possible to perhaps over-interpret the meaning of lower weight-at-age and body condition. The number of fish in the stock of course has a major impact on the spawning stock biomass," says David Gilljam, researcher at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) and one of the researchers who produced the basis for the stock assessment used in the ICES advice.

What has had the greatest impact on the spawning stock biomass declining – the individual body weights of the fish or the number of fish in the stock?

"At the moment, we can't determine which is the main factor. I would say that it is a combination of both that has contributed to the decline," says David Gilljam.

According to him, it is important to define which period of the time series you are looking at.

"Depending on when you look, the different factors have slightly different weights relative to each other," he says.

Increased catches - decreased condition

From the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, the spawning stock biomass grew strongly. During the 1990s, fishing pressure doubled and catches increased from just over 30,000 tons to around 60,000 tons.

Around the turn of the millennium, the average weight of herring fell dramatically and then levelled off at new lower levels. At that point fishing pressure doubled again and catches rose from 60 000 tonnes to a peak of 120 000 tonnes.

“Then fishing pressure was reduced again, and during the last 3-4 years we have had catches of around 70,000 tonnes per year. Despite this, the spawning stock biomass continues to decline. In recent years, we have also seen record low condition in herring," says David Gilljam.

Condition is the herring equivalent of human body mass index (BMI), and is a measure of the weight of herring based on their length, not their age. The condition index for larger herring (16-20 cm long) in the Bothnian Sea dropped to a record low of 0.47–0.53 in 2021. But already the following year, condition increased again, to 0.51–0.58.

Furthermore, the latest sampling of commercial fishery catches shows that condition increased further in the winter 2022/2023. At the same time, the condition of herring in several other length classes has increased in recent years.

Is it not reasonable to assume that the sharp decline in spawning stock biomass is mainly due to the fact that there are fewer herring in the stock now than before?

“The number of individuals in the stock has definitely decreased significantly. But again, to be able to answer that question as well and comprehensively as possible, to be able to give the whole picture of how much different factors affect, we need to investigate it in more detail and look at both the effects of fishing and things like changes in the marine environment and food availability," says David Gilljam.

Many argue that the situation for herring is so acute that action is needed now.

"I agree that we must do something right away. We can influence some changes in the environment of the Baltic Sea, but it involves very long processes. Fishing is something we can influence here and now, from one year to the next," he says.

Fishing mortality doubles

Earlier this year, the European Commission proposed an end to all targeted herring fishing in the Gulf of Bothnia and the central Baltic Sea next year. The Council of Ministers, including Swedish minister Peter Kullgren, rejected the Commission's proposal and instead decided on a catch quota of 55 000 tonnes of herring in the Gulf of Bothnia.

This represents a 31 percent reduction compared to this year – but also means that catches will be at the same level as they were in the early 2000s. One important difference compared to then is that today the herring spawning stock biomass is only half as large as it was then.

“In practice, this means that fishing mortality, i.e. the proportion of the stock that is killed by fishing, will be about twice as high next year as it was 15-20 years ago," says David Gilljam.

Herring in the Gulf of Bothnia have gone downhill in recent years. What indicates that things will be better this time?

“Not much. It looks bleak for the herring. The risk of the spawning stock biomass falling below the critical level Blim next year is far too great to continue fishing,” says David Gilljam.

So, fishing should have been stopped?

“I think so. According to ICES, the risk of ending up under Blim next year is higher than five percent, so we should not fish any more. From my perspective, there are not many other ways to interpret what is said in the management plan.”

Text: Henrik Hamrén

Last updated: December 6, 2023

Source: Baltic Sea Centre