Nitrogen fertilisation of forests – and of the Baltic Sea

Sweden should increase nitrogen fertilisation of its forests — even in the southern parts of the country — according to the government’s forest policy inquiry. However, increased fertilisations is a also expected to lead to higher inputs of nitrogen to the Baltic Sea – inputs that Sweden has committed to reducing under the HELCOM Baltic Sea Action Plan, the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive, and the Water Framework Directive. “If leaching from forests is allowed to increase, nitrogen loads from other sectors must be reduced even more,” says researcher Bärbel Müller-Karulis.

Carbon dioxide uptake by forests is an important part of the Swedish carbon budget. Yet in recent years, carbon uptake in Swedish forests has declined while demand for forest raw materials has increased.

To increase forest production, the government's inquiry "A robust forest policy for active forestry" (En robust skogspolitik för aktivt skogsbruk) recommends expanding the nitrogen fertilisation of forests. This would be achieved by removing the regional limits on fertilisation, particularly in the south of the country, and by relaxing the restrictions on fertilisation in highly productive areas. The report also calls for updated fertilisation guidelines, expanded advice, and a narrowing of protection zones around sensitive biotopes from 25 to 10 metres (though not for lakes and watercourses), arguing that today's fertilisation technology has become more precise.

Overall, the investigation estimates that these measures could increase the area of forest fertilised annually from 15,000 hectares to 80,000 hectares, a level last seen in 2010.

However, this is expected to increase the nitrogen inputs to the Baltic Sea caused by forest fertilisation from an estimated 80–170 tonnes per year to 400–900 tonnes per year.

"900 tonnes correspond to just under two per cent of Sweden's total nitrogen loads from land to the Baltic Sea. However, through HELCOM's Baltic Sea Action Plan, we have committed to reducing rather than increasing these loads," says Bärbel Müller-Karulis, a researcher at Stockholm University Baltic Sea Centre who studies nutrient loads and their effects in the Baltic Sea.

Where in Sweden the increased nitrogen leaching occurs is crucial in determining its effect on the sea. The central part of the Baltic Sea, known as the Baltic Proper, is the area most affected by eutrophication. While Sweden currently meets its commitments under the Baltic Sea Action Plan with regard to nitrogen emissions to the other basins, annual emissions to the Baltic Proper still need to be reduced by a further 9,400 tonnes.

"For the Baltic Proper, it’s crucial that the nutrient loads don’t increase. Increased nitrogen leaching from forests would have a greater impact there than if it occurred in northern Sweden", says Bärbel Müller-Karulis.

Regional restrictions may be removed

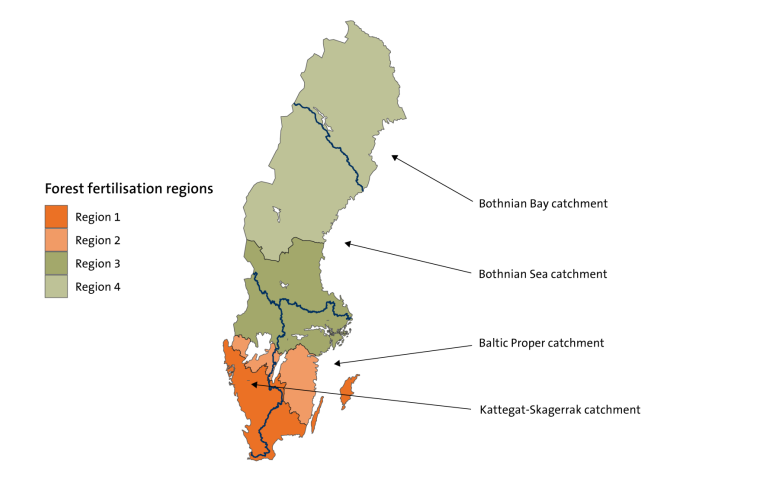

Nitrogen fertilisation of Swedish forests has been regulated since 1977. Current rules divide the country into four regions, with stricter limits in the south (regions 1 and 2) than in the central and northern regions (regions 3 and 4).

This division is due to historically higher levels of atmospheric nitrogen deposition in the south. High atmospheric deposition enriched soils with nitrogen to an extent that access to nitrogen was not considered a limiting factor for forest production in the south of the country.

However, as atmospheric nitrogen deposition has gradually decreased over a long period of time — thanks also to better exhaust purification and reduced coal combustion — the inquiry suggests to abolish the regional division entirely and the government’s investigator proposes to expand forest fertilisation also to regions 1 and 2. He argues that while nitrogen deposition in southern Sweden is sufficient to maintain current forest growth, fertilisation could further enhance productivity.

The investigator estimates that removing regional restrictions, together with the other measures suggested, would lead to around 80,000 hectares of Swedish forest being fertilised each year. However, this estimate is uncertain, according to experts at the Baltic Sea Centre. In the report "Measures for increased forest fertilisation" (Åtgärder för ökad skogsgödsling) published earlier this year, the Swedish Forest Agency estimates that, even with regional restrictions remaining in place, the area that can be fertilised each year could ultimately increase to 78,000 hectares.

"If the Swedish Forest Agency estimates that almost 80,000 hectares can be fertilised in regions 3 and 4 alone, it is highly likely that the total area will exceed that figure if the same rules for forest fertilisation will apply in regions 1 and 2. The consequences in terms of nitrogen loads to the sea are therefore highly uncertain," says Bärbel Müller-Karulis.

Good ecological status not being achieved

Regions 1 and 2 correspond to the catchments of the Öresund, Kattegat, and parts of the Baltic Proper. If restrictions on forest fertilisation in these areas are lifted, there is a risk that the nitrogen inputs to the Baltic Proper, which is most affected by eutrophication, will increase.

Also, many lakes and coastal areas in these regions fail to achieve ‘good ecological status’ according to the EU Water Framework Directive because of eutrophication. Much of this area is also designated as nitrate-sensitive, meaning that special rules apply to activities such as the spreading of manure in agriculture.

"There are several reasons not to increase nitrogen leaching in these areas, and it would make sense to harmonise the various fertilisation regulations," comments Bo Gustafsson, a researcher at the Baltic Sea Centre and head of the modelling group at the Baltic Nest Institute.

Which inputs should be reduced?

If nitrogen inputs from the forests are to rise, the inputs from other sectors, such as agriculture, will need to be cut back even more than planned for Sweden to meet the targets set out in the Baltic Sea Action Plan and the Water Framework Directive. At the same time, Gun Rudquist, policy director at the Baltic Sea Centre, notes that there is considerable political pressure to expand food production in Sweden as part of efforts to strength nation preparedness and food security.

"The latest Swedish food strategy prioritises increased production as an important part of the ongoing discussion on preparedness for crises and war," she says. "However, there is far too little discussion about what production should increase and its environmental impacts."

According to Benoît Dessirier, a researcher at the Baltic Sea Centre studying nitrogen leaching from agricultural land, increasing agricultural production while reducing emissions is not an easy nut to crack.

"It is possible to reduce nitrogen losses to water to a certain extent through precision fertilisation, catch crops and buffer zones, for example," he says. "But achieving the required reductions to the Baltic Proper from the agricultural sector, major changes are needed. This could involve taking land prone to leaching out of production — a move that would conflict with the goal of increased production — or shifting to different crops and reducing feed and animal production."

In a recently published report, Sweden’s water authorities assessed the potential impact of various measures to reduce nutrient leaching in agriculture and identified precision fertilisation as having greatest potential. Expanding precision fertilisation in the southern Baltic Sea water district would cut nitrogen loads to the Baltic Sea by roughly the same amount as the increase expected from forest fertilisation – about 600 tonnes.

"Once the obvious measures targeting major sources have been implemented, achieving the environmental objectives for eutrophication in the Baltic Sea becomes increasingly challenging. Forest fertilisation is a clear example how different environmental goals and societal interests can collide, requiring difficult trade-offs from decision-makers. Here, we researchers have an important role in developing tools that allow for a comprehensive assessment," says Bo Gustafsson.

Text: Lisa Bergqvist

Last updated: November 6, 2025

Source: Baltic Sea Centre