Fact Sheet: Can changing our diets help the Baltic Sea?

2018.06.25: This fact sheet describes different scenarios on how trade, production, and consumption affects eutrophication in the Baltic Sea.

Agriculture is the single largest source of human-related nutrients to the Baltic Sea, contributing about 40% of total waterborne nitrogen inputs and 30% of total phosphorus inputs.

In the catchment, most nutrients cycle through livestock; a major portion of mineral fertiliser and livestock feed that is imported is transformed into manure. About 70% of crop production is fed to livestock, while only 30% is consumed directly by people. In spite of all that arable land used for producing feed, this does not fully meet the needs of livestock. About half of nutrients consumed by livestock are imported (mainly soy from South America) adding to the total flow of nutrients in the catchment.

Regions with large numbers of livestock in relation to agricultural land often rely on imported feed because there is not enough local production. In these areas, proper manure management can be difficult because the amount of nutrients in livestock manure exceeds what local crops require. This situation can lead to over-fertilisation and nutrient surpluses, which increase the risk of nutrient leakage to the environment.

Food is a global business

Globally, the consumption of livestock products has increased drastically since the mid-1990 and continues to rise. This increase in consumer demand has impacted the agricultural systems in the region, but because food is now a global business, there is often no regional link between consumption and production. As a result, reducing the consumption of livestock products in the Baltic Sea catchment could lead to different outcomes depending on how farmers respond.

- First, what if people in the Baltic Sea catchment consumed fewer livestock products that were produced outside the catchment?

This would only reduce the import of livestock products and would have no direct effect on the risk of nutrient leakage to the Baltic Sea.

- Second, what if people in the Baltic Sea catchment consumed fewer livestock products that were produced in the catchment?

In this case, farmers could keep producing as much as today and just sell it elsewhere because of strong global demand. In this situation, reduced consumption of livestock products would not reduce in the risk of nutrient leakage to the Baltic Sea.

- Third, what if the consumption of livestock products from the Baltic Sea catchment was reduced and farmers cut back on their livestock production?

Over time, this could reduce the risk of nutrient losses to the sea, but it depends on how the land previously used for livestock is used. Farmers could cultivate the land and grow a larger share of crops for human consumption. This could increase the total production of plant-based food in the Baltic Sea catchment, because crop production generally uses fewer resources than livestock production.

That said, producing different crops can either reduce or increase the risk of nutrient leakage to water. For example, rearing of beef and dairy cattle is closely connected to grass production which often has lower nitrogen losses than annual crops.

- Fourth, what if the production and consumption of livestock products from the Baltic Sea catchment was reduced and agricultural land used for feed is taken out from production?

Over time, if the production of livestock products was reduced and agricultural land used for feed is taken out from production, this could reduce the risk of nutrient losses to the sea. However, there are many reasons why such actions are neither realistic nor desirable.

Food production in the region is vital not only from a food security perspective, but also for nutrient recycling, biodiversity, rural development, and cultural values. From the business perspective of farmers, taking land out of production is a less likely development.

Large variation in environmental impact

On top of these different consumption-production scenarios, it is also important to consider that:

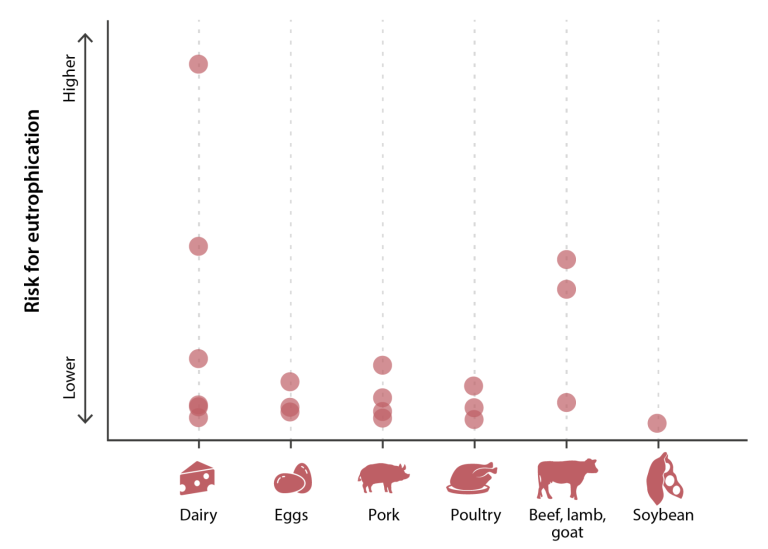

- the environmental effects of livestock production are highly variable among regions and types of products.

- the risk of nutrient leakage depends on local conditions.

Some livestock systems may have low nutrient pollution per kilogram of food, but high nutrient pollution per area. Thus, it is important consider the total amount of nutrient pollution and the risk of nutrient leakage where livestock are located.

Other benefits of reducing production and consumption

In addition to reducing the risk of nutrient leakage from agriculture, there are a number of other health and environmental benefits to reducing the production and consumption of livestock products.

- Reduced resource use

Producing and consuming livestock products uses more resources (water, fossil fuels, nitrogen, and phosphorus) per amount of protein or calories compared to crop products. For example, in a high-density “industrial” system, producing one kilogram of pork meat requires about four kilograms of feed that could otherwise be consumed by humans. If we ate the food rather than feeding it to livestock, we would be able to feed more people per area of farm land. About ten times more energy, from fossil fuels for example, is needed to produce proteins in meats compared to proteins in legumes.

- Reduced nutrients in sewage

Adults do not use most of the nitrogen (in protein) and phosphorus in food (especially dairy products) that they consume. As a result, these nutrients are excreted and enter sewage systems. Nutrients that are not removed by sewage treatment enters surface water as effluent. If people reduced their total protein intake, there would be minor reductions in nitrogen and phosphorus from sewage.

Regardless of human diets, no current technology removes all nutrients from waste water effluent. Improving sewage treatment is an effective way to remove nitrogen and phosphorous from wastewater entering in lakes and rivers that drain to the Baltic Sea.

Sewage management practices have improved substantially in the past few decades, but systems and capabilities vary greatly around the region. For example, nitrogen removal efficiency in centralised sewage treatment facilities is between 34% (Latvia) and 92% (Denmark). Phosphorus removal efficiency is between 63% (Latvia) and 97% (Finland, Germany, and Sweden).

- Improved human health

A healthy, balanced diet includes proteins. Livestock products are an important source, not only of protein, but essential vitamins and minerals as well. However, in the EU, average protein consumption is 70% greater than what our bodies need. Overconsumption of protein alone is not a health issue, except that this protein is often contained in high-fat foods, red meat, and processed meats. Consumption of high-fat foods increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and consumption of red meat and processed meats increases the risk of certain cancers.

No quick or easy solutions

Among the public, there is low but growing awareness of the environmental effects of livestock husbandry on the environment. Focusing on consumption could be more feasible than focusing on production, because consumers are more likely to change their dietary habits than livestock farmers are to reduce their operations. Livestock production is important to rural livelihoods and economies.

There is strong and growing demand for livestock production in many areas, such as East Asia for example, and trade deals encourage the export of these products. However, reducing the consumption and production of livestock-based food is fraught with political, social, and economic challenges. Dietary habits derive from complex social, cultural, and behavioral factors and governments often are reluctant to tell people how to eat or tell farmers what to produce.

Research shows that consumption taxes could be effective in reducing consumer demand for meat and dairy products. Other options include public information campaigns, improved food labeling, and point of purchase information, but, the effectiveness of these approaches needs further research.

Last updated: March 30, 2022

Source: Östersjöcentrum