BLOG: Risk before hazard – a potential risk?

2018.10.22: A more risk-oriented chemicals legislation in Europe could potentially constitute a real… risk. And that would be hazardous.

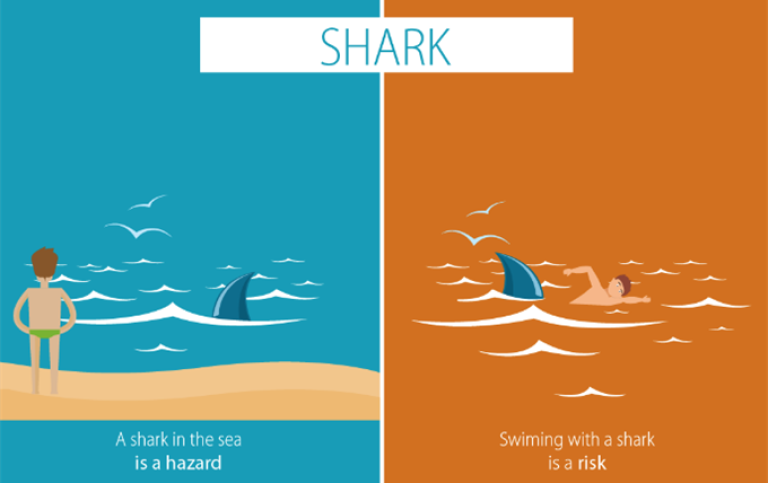

A shark in the sea is a HAZARD. Swimming with a shark is a RISK. Lightning is a HAZARD. Standing under a tree during a thunderstorm is a RISK.

When the EU Food Safety Authority (EFSA) explains the two most disputed words in Europe's chemical legislation REACH, they use an infographic that is so straightforward that it has a touch of pointer books for daycare children. And that's probably wise. The more difficult something is to comprehend, the easier the explanation should be.

The tricky thing with the words hazard and risk, is that they on an intuitive level mean almost the same thing. Few would oppose the claim that it is hazardous to swim with a shark, or that it is hazardous to stand under a tall tree during a thunderstorm. In everyday speech, and in our minds, these are correct statements. But when it comes to chemical policy – they’re not.

And it doesn’t get any easier in translation. Swedes are fairly good at understanding English. But when things get complicated and a more profound understanding is required, many of us tend to go back to basics and translate to our native language.

The English noun risk is primarily associated with the Swedish word risk, but it may also mean fara (hazard). And the word hazard is usually translated into fara (hazard), but can also mean a risk.

In the REACH legislation, both of these balls are kept in the air at the same time, which has given rise to many and complicated discussions in academia as well as in politics.

Briefly, it can be explained as follows: When REACH is used to determine whether a particular substance is to be banned or not, hazard and risk are assessed separately. A substance can thus be hazardous, but it only poses a risk if we are exposed to it in high enough doses.

On the one hand, legislation is based on minimizing hazard, for example by identifying and registering substances of very high concern. The criteria for putting a substance on this list are based solely on assessment of how hazardous the substance is.

On the other hand, REACH also allows for a certain degree of acceptable risk. If a substance is to be banned or not, will also be determined by the amount of risk associated with using it.

An example: In Sweden, some low-energy light bulbs still contain mercury, which is a hazardous substance for humans. But the risk of being poisoned when we handle the bulb is considered acceptable. As long as we do not crush it and breathe in the mercury fumes, it is completely harmless.

For politicians involved in European chemicals issues, those types of balances are commonplace. But it's no easy job. In addition to keeping track of the recent science and what substances that actually circulates in society – for instance in goods and products – they also must pair lobbying from strong societal parties that have completely opposite opinions about how to use the words hazard and risk.

On the one side we have the environmental organizations (and quite a large part of academia) who have the more intuitive approach; using hazardous substances is hazardous. In the best of worlds, there are only harmless substances in our daily lives. But since that is a utopian scenario, we should at least do our utmost to limit the use (and amount of) hazardous substances.

On the other side we have the chemical industry - from manufacturer to dealer – that advocate the more pragmatic and risk-oriented perspective; as long as exposure to a hazardous substance is limited or completely eliminated, it is not a hazard.

It is probably fair to say that industry so far has been more successful in conveying and getting hearing for its more risk-oriented approach. At the same time, more and more voices are heard, not least in academia, which warns of an overly risk-oriented use of the REACH legislation. They argue that such a legislative approach does not play well with the global market economy, since risk is much harder to assess than hazard, and since goods and services change owners and travel across the globe like never before, while Europe's chemical production hits new records every year.

The struggle for which word to weigh heaviest within REACH legislation is far from being decided. Probably it will never be solved. Both words will remain, and it becomes the responsibility of politicians to determine their respective denominations.

When words are against words, it's it’s often helpful to turn to the facts of the matter.So hopefully, science will continue to play an important and growing role in those considerations.

Recently, Baltic Eye researchers Emma Undemann and Damien Bolinius published a policy brief on chemicals in consumer articles. Their perhaps most important conclusion is that we know less and less about the increasing amount of new and unknown substances that end up in our everyday lives. And if we don’t know what is hazardous, it's hard to protect ourselves from the risks.

In light of that, a more risk-oriented chemicals legislation in Europe could potentially constitute a real… risk.

And that would be hazardous.

Text: Henrik Hamrén

Last updated: August 5, 2022

Source: Östersjöcentrum