The volcanic eruption that left its mark on both landscape and science

A new article by Simon Larsson at the Department of Physical Geography, Stockholm University, presents the story behind the discovery of the Askja volcano in Iceland and the subsequent studies of the ash that spread from the eruption in 1875. The studies of the ashes have been important for scientific progress in geosciences — advancements that continue to resonate today. The article is published in Dynamica, the university library’s new open science platform.

An Eruption's 150th Anniversary

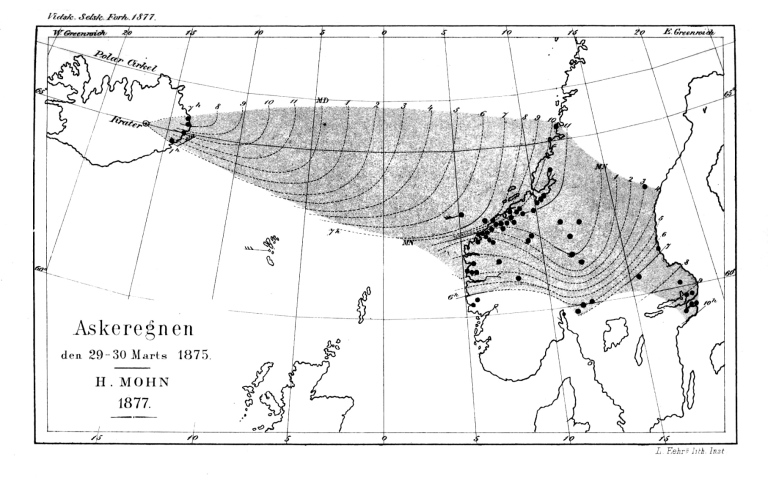

This year marks 150 years since the powerful Plinian eruption of Askja in Iceland. The ashes from the eruption reached as far as Stockholm. Observations of the ashfall were collected from the North Atlantic, Norway, and Sweden in what can be considered an early example of citizen science. The gathered data was used to create the first detailed map of the geographical spread of volcanic ash, visualising the event hour by hour. Ash samples were also collected from Hagaparken in Stockholm and examined by geologist and member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld, who later led the Vega Expedition.

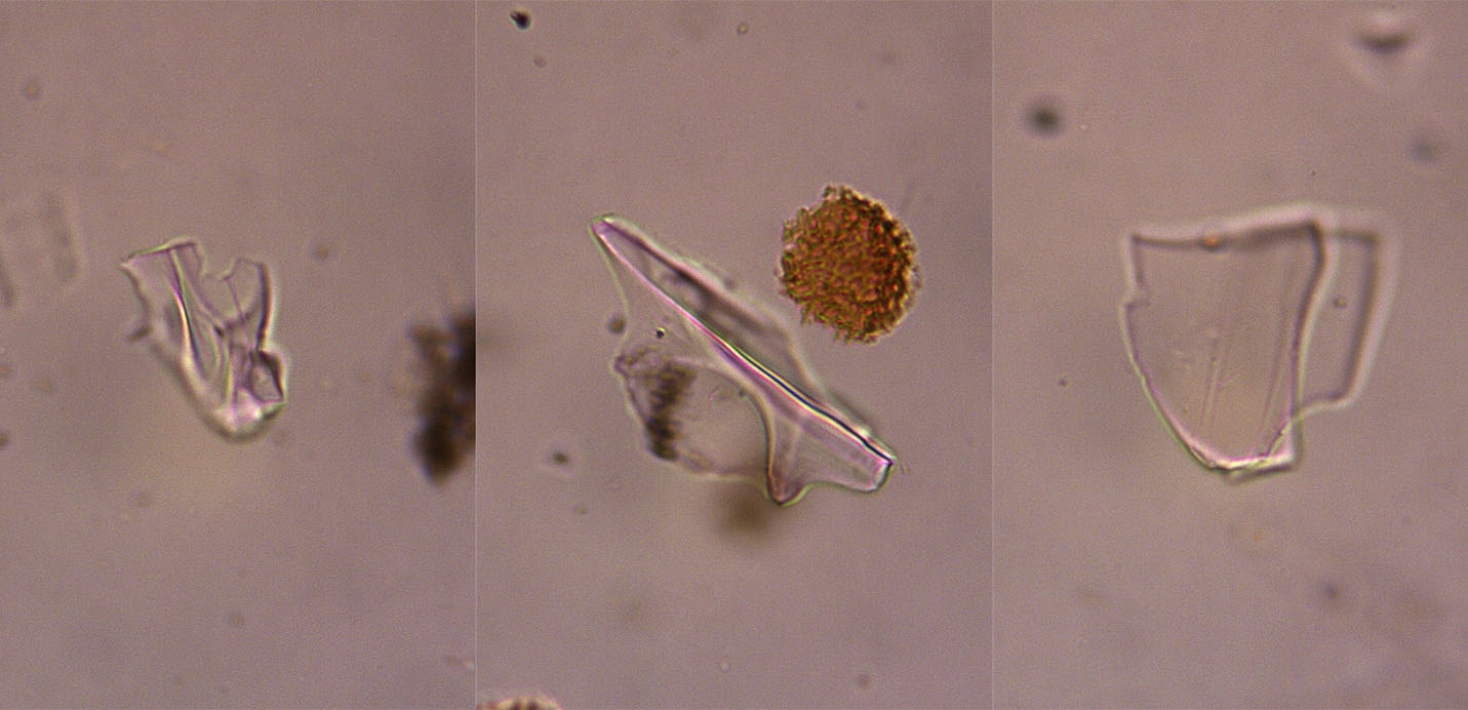

“This eruption has been significant for scientific breakthroughs in various geoscientific fields. Today, understanding the dispersal patterns of volcanic ashes is vital for risk assessments worldwide. Examining volcanic ash under a microscope, as Nordenskiöld did, remains a key method when tracing historical and prehistoric eruptions,” says Simon Larsson.

When Askja erupted in the winter of 1874–1875, the volcano — located in Iceland’s sparsely populated interior — was still unknown even to locals. The eruption peaked during Easter weekend 1875, and several expeditions were made to the area after the event. The story of these explorations is summarized in the first part of the new article.

“I hope this story appeals even to those not specifically interested in volcanic ash studies, so I’ve introduced it in a way that most readers can engage with,” says Simon Larsson.

A Research Tradition at Stockholm University

Ash from the 1875 Askja eruption was rediscovered in Icelandic bogs in the 1930s when Sigurdur Thorarinsson conducted his doctoral studies at Stockholm University College (later Stockholm University). This marked the beginning of tephrochronology — a dating method that uses volcanic ash to determine the age of geological deposits such as peat, lake sediments, and glacial ice. The word tephra comes from the Greek word for ash and refers to all solid particles ejected during a volcanic eruption.

“Just as Thorarinsson found ashes from this eruption in Icelandic bogs, we’ve found it in a lake in Jämtland. I first sampled it for my master’s thesis in 2014 and revisited it in 2024 as part of my current postdoc research. Today’s technology allows us to identify volcanic ash by its geochemical ‘fingerprint,’ since each eruption tends to have a slightly different chemical composition,” explains Simon Larsson.

During the 2000s, tephrochronological research at Stockholm University has been led by Professor Stefan Wastegård in Quaternary Geology, with many international collaborations and publications. The research group is called "SUQuaTeSt": Stockholm University Quaternary Tephra Studies.

Interest in this research surged in 2010 when the Eyjafjallajökull eruption in Iceland produced an ash cloud that spread across Northern Europe and disrupted air traffic. Questions arose about the eruption frequency and ash composition — answers to which can be found through tephrochronology.

Open Science on the Dynamica Platform

The article is published via the open science platform Dynamica, developed by Stockholm University Library and SciFree, a company that builds tools for open research publishing.

“I believe universities should have more control over scientific publishing, rather than a few large companies charging for the publication of taxpayer-funded research. For something to be published in Dynamica, it must undergo the same kind of peer review as in scientific journals, but there’s no editor acting as a middleman — researchers own the entire process. I hope more researchers at Stockholm University choose to publish through Dynamica,” says Simon Larsson.

Contact

Simon Larsson

E-mail: simon.larsson@natgeo.su.se

Last updated: September 15, 2025

Source: Department of Physical Geography