Today was the warmest day on Iceland so far: blue sky with white clouds, the sun was shining and the strong wind that we had experienced during the past days had become much weaker. The backside of the sunny and comparably calm day was however the appearance of hundreds of irritating mosquitoes that seemed to pop up everywhere. All of these are non-biting midges and the only thing they do is being annoying – they swarm all over, and creep into the ears, the mouth, the nose, and behind the sunglasses!

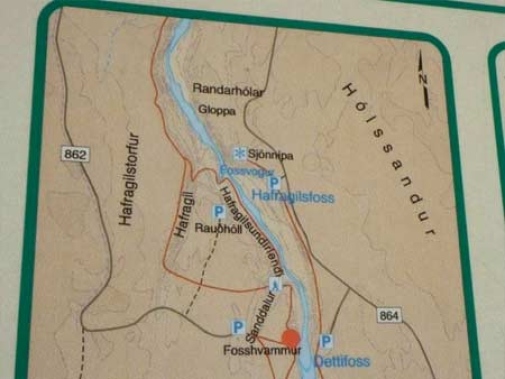

The area around the picturesque waterfalls of Dettifoss and Sellfoss, and the lava field at Dimmuborgir were today’s focus. We looked at lava stones, which have a nicely polished surface on one side, and rough and edgy surfaces on the other sides. The polish has been made by the strong wind that sweeps over the land surface and carries small sand- and silt-sized particles, which act like a scrub. Standing here for a few minutes facing the wind would make any face scrub unnecessary!

The river has created a deep canyon, exposing beautiful pillar basalt. At one place the canyon cuts right through the middle of a small volcano, splitting it into half and thus exposing the vertical channel were the magma had been rising and gradually cooling.

So much still needed to be done for our film project, and we were not sure at all that we would manage due to the very tight schedule. We would have needed several days to film all these great sights: the waterfalls, the basalt columns, the wind-polished lava stones, the old volcanoes, the tiny flowers, and the stunning rainbows that became visible in the mist close to the waterfall. Unfortunately the schedule made all the detailed filming impossible, because we had so many other ‘to do’ things on our list; we needed more close shots of the students drawing and studying rocks and minerals, and we needed some interviews with the students too. For the interviews we needed a place with no or little wind and this was not easy in an area where the wind was almost a continuous companion. Nerys and I finally found a calmer spot at Dimmuborgir, where the lava field had created sheltered areas with small hollows and cavities, and where the ample tree birch vegetation provided protection from the wind. We had exactly one hour left to conduct the four interviews and managed with a margin of less than five minutes before the bus left for Akureyri, from where we were flying back to Reykjavik.

Imagine how I felt at the airport check-in, when the clerk told me that I was not booked on today’s 19:25 flight, but on tomorrow’s! For a couple of seconds I thought the world would go under – I would not be able to get on this flight, I would miss my connecting flight from Reykjavik, I would get home later than planned and I would have to re-book the whole trip. But sometimes luck is on one’s side! One single seat was still available on the small airplane and with the help of my credit card I managed to get the seat.

Reykjavik was covered in thick clouds when we arrived, and temperatures were below 10 degrees C. It reminded me of years ago when I had visited the city and everything was just grey and dark and not at all inviting.

After a quick shower and a change of clothes we left for the Pearl restaurant where we had planned our farewell dinner. The restaurant is situated slightly above the city and is constructed as a big futuristic, turning bulb on concrete pillars. The food was delicious, and the view over the city was great, despite the fog. I am not sure whether Nerys could really enjoy the food and the view. She had spotted Bon Jovi at a table next to us and got all excited seeing him, since she had been his fan since she was a kid and had also just been to one of his concerts. Or, maybe it was just a person who looked like Bon Jovi? By the time we had the courage to go over to his table to find out, he had left.

Iceland is a wonderful place and definitely a place to come back to: stunning landscapes, nice people, good food, and so much more to see. I am definitely going back soon.

Husavik and its fault zone were also the focus of day 3 of the field trip. However, Nerys and I decided that we had seen enough rocks for the moment and that we would need more typical Iceland shots for the film. Therefore we drove around with our rental car and tried to find scenic farms, beautiful mountain views, rivers, Icelandic horses, sheep, cows and flowers.

There is s much to see in the area south and east of Akureyri and around Husavik – the open ocean, the cliffs, the wide green valleys dotted with farms, torrential water falls, meandering rivers glittering in the sun shine, small patches of mountain birch forest, snow covered mountains, grazing sheep and cows, farmers working their fields, and new born foals running and playing with their mothers.

Just after lunch we joined the group again to look at the ‘end’ of the fault, which is exposed in a cliff along the coast. Again we went for a long walk, crossing several small creeks, which drain into the sea. The coastal sand is made up of fine-grained black lava, and is interspersed with white shell fragments and rounded pebbles originating from volcanic rocks. It was quite tough to walk along the beach. The wind was very strong and the terns, which were breeding or protecting their youngsters nearby, were very aggressive. However we were rewarded for all the dangers by the most beautiful zeolite minerals, which grow in the cavities and fractures of the lava rocks.

Stop #2 was at the water-monitoring site above Husavik. For the last 10 years, Alasdair and his group have regularly been monitoring and measuring the chemical content of the water running out of a 1500 m deep borehole here. They do this to see how and if the chemical content of this deep water (the aquifer is at 1200 m depth) changes before and after an earthquake. By having a long monitoring series, it might be possible to draw precise conclusions on how and why the chemistry of the deep water changes in relation to an earthquake, and to see if these data sets might be used in the future to better understand processes deep in the crust in connection with an earthquake. The two bathtubs filled with hot water from the borehole, are a fun part of the monitoring station. People can come here to enjoy a bath in the warm water, to relax and to contemplate the beautiful view over the bay of Husavik. Of course many of the students had a quick bath!

Husavik and its surroundings are so beautiful, and it is therefore hard to imagine that the town is actually situated on one of the most dangerous fault zones. But it has been some time since the last large earthquake, which occurred in the year 1872, and had a magnitude of 7 on the Richter scale. The last earthquake happened nine years ago, but it was of a lesser magnitude. This is probably the reason why people, who are living here, are not too afraid of earthquakes.

The second last stop of the day was again along the beach. For a change, and after having seen so many volcanic rocks, we now checked out up-lifted beach/shallow marine sandstones with distinct shell layers, ripples, cross-bedding and nice cut and fill structures. Unfortunately we could not spend too much time here, because the students had been booked on a whale watching tour at 5 pm. However we managed to kidnap Alasdair for the long overdue interview we wanted to make with him about his research. The big challenge was to find a quiet spot with little wind … not an easy task on Iceland. We tried at several locations and ended up on a slope overlooking the harbour of Husavik – just right in the middle of the fault zone. A great place for an interview about earthquakes and what damage they can create.

A zip in the highlands

July 5, 2011

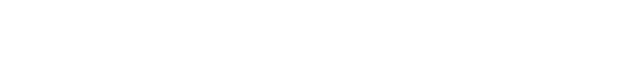

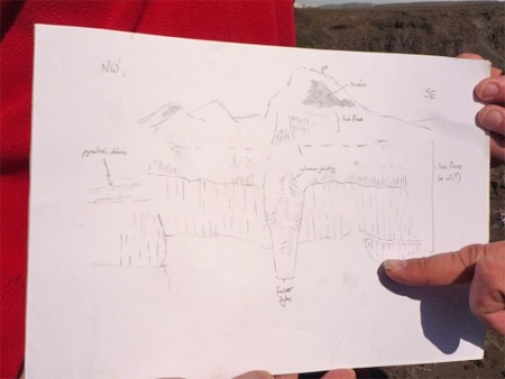

Tens of kilometres long, several meters wide and more than 10 meters deep – this was one of the most impressive geological features I had ever seen. This huge zip in the middle of a desolate highland southest of Husavik is a gigantic fault, which runs more or less parallel to the Krafla volcanic field, the area we visited yesterday. Both zones form part of the mid-ocean ridge on which Iceland is situated.

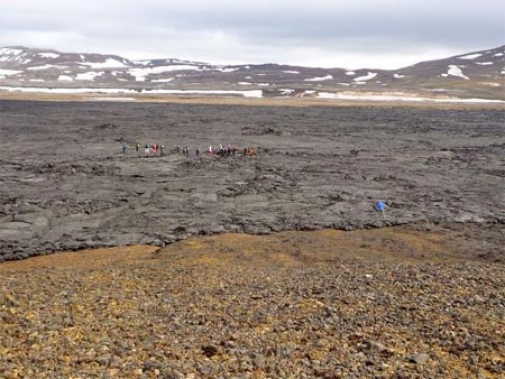

The small gravel road leading up into the vast highland could easily be managed by our bus and by our bus driver, except for a short stretch, where road works made a detour necessary. Road works – this sounds almost ridiculous in this desolate place, but obviously there are plans to build a geothermal power plant far up in the highland, which will be used to run a future aluminium smelter in Husavik. The clayey soil close to the gravel road was soaked with water, and it came as now surprise that the bus first started to glide and finally got stuck! Our poor students became really frightened and thought that the bus would turn over, but they were told that Icelandic busses never turn over, and this calmed them down a bit. Luckily the cater pillar driver volunteered to help us out and pulled the whole bus out of the sticky clay. After a few more kilometres through lava fields and sparse vegetation, followed by a long walk over a hummocky field, we arrived at the spectacular fault. The view on the fault from higher ground was really spectacular: a wide crack with huge dissected and tumbled rocks on each side, winding through the flat landscape like a huge snake. One could really feel the power of the continental plates pulling apart, building up strain and stress in the rocks, and then a sudden burst. What a noise it must have been, when the rocks started to crack and tumble over.

The students ended this long day with a visit to one of the hot springs, while Nerys and I continued in our rental car to get some good shots of the small town of Husavik and the surrounding landscape. Husavik is well known for its whale safaris and thousands of tourists come here each year to sail out with the former whaling boats to see the whales.

Heavy grey clouds and rain met us this morning when we left Akureyri for the Krafla volcanic field. On our way around Eyarfjördur and through the Fnjóska and Ljósavatn valleys, the landscape is heavily shaped by glacial processes: large end moraines indicating the still-stand of the ice margin during the deglaciation, U-shaped valleys showing glacial erosion, and gravel deposits originating from the large rivers, which drained the former ice sheet. But these glacial landscape features go hand in hand with volcanic processes, which are present all over Iceland and show up as thick ash beds and/or vast lava fields.

Today’s topic was the spreading of continental plates, how the American and Eurasian plates move apart, and which types of geological features this rifting created and is still creating. One of the best places to see this is the Krafla volcanic field, a gorgeous place to spend a whole day. Dark lava fields, cracks and fissures, bubbling sulphur pools, orange-yellow ridges, and steaming soil still testify for the volcanic eruptions and earthquakes that took place here some 30 years ago. Much has been written about the famous Krafla fires, which occurred during the years 1980-1982 and which created these enormous black lava fields covering 35 km2.

The large rift, which separates America from Europe, is spectacular and really illustrative – a deep fissure, partly covered by collapsed lava and volcanic rocks, and partly completely open. It is possible to stand here having one foot in Europe and one foot in America!

Now the area seems relatively quiescent, but the hot steam, which emerges from cracks and fissures clearly shows that the next eruption may come any day. It is quite dangerous to go too close to these hot steams, where the smell of rotten eggs merges with sulphur precipitates and hot lava rocks. It is hard to imagine a more dynamic geological place than Iceland.

Today we also started shooting for the department film. To be more exact – Nerys was filming, and I was acting as her assistant, carrying the tripod and pointing out what I thought were really cool geological features.

Lava, lava and nothing but lava

July 2, 2011

Today was the last day of the first excursion. The weather just seems to get better and better, with less clouds and much more sun, and probably the highest temperatures since coming to Iceland. Dettifoss, the large waterfall northeast of Akureyri, and the hot springs close to Myvatn were the most important stops today.

The road from Myvatn to Dettifoss leads through a desolate brown and grey coloured landscape made up of lava, lava, and glacially reworked lava. Huge end moraines indicate where the Icelandic ice sheet once halted on its final retreat. Wind-polished rocks and tiny arctic plants in sheltered areas show how harsh climatic conditions are here.

The waterfall at Dettifoss is impressive – a huge mass of water plunges into a deeply incised canyon, which is lined with beautiful vertical basalt columns. How long time did it take to create this 100 m deep canyon? How much water must have run through here during the last thousands of years? How old are the basalt columns?

A section through a remarkable feeder dyke of the Sveinar-Randarhólar crater is exposed alongside the canyon, and surrounded by horizontal black and red ash layers to the right and left. This eruption is dated to around 6000-8000 years ago, and gives us a maximum age for the incision of the canyon. It is amazing that such a deep canyon formed in such a short time.

Closer to Myvatn the soil emits steam and its hue changes to a yellowish brown and orange yellow. This is the place where sulphur appears at the surface and where a smell of rotten eggs fills the air. But it is also the place of the famous hot springs used for geothermal power production, heating and recreation. A well-known spot are the pools with hot water close to Myvatn, which attract tourists and geology students equally.

The first green patches appear around Lake Myvatn. It is one of Iceland’s larger lakes, a paradise for bird watchers and an oasis in the middle of all the dark lava fields. The lake is surrounded by green meadows with grazing sheep, lovely birch and larch forests, and dotted with small farms and villages. The tourist season has just started and the cottages, guesthouses and hotels will soon fill up.

This evening the first group of students will leave and the second group will arrive to Akureyri. The next four days will be spent exploring volcanoes, lava fields, hot springs, faults and rift zones, and with filming the students and the great landscapes.

This entry was posted in Iceland 2011, Travels and tagged Department of Geological Sciences, Iceland, Stockholm University. Bookmark the permalink.