Creative research environment attracts physicists and astronomers to Stockholm

In 2008, the Oskar Klein Centre in Stockholm was founded to tackle the greatest problems in astrophysics and particle physics in an interdisciplinary manner. It is now celebrated as a rich and rewarding research environment that attracts internationally leading researchers, including Nobel laureate Frank Wilczek.

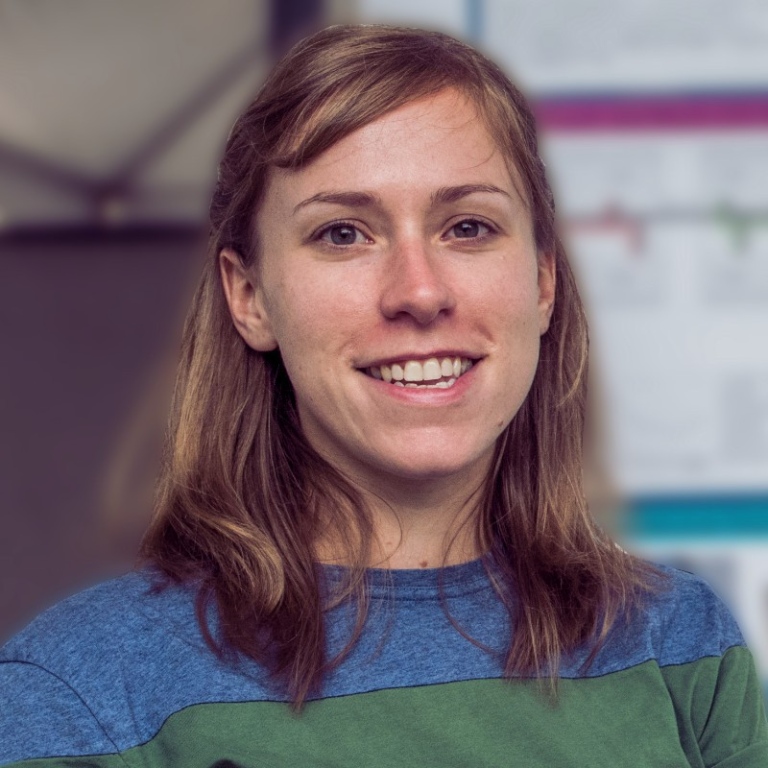

“Previously, we pretty much only met our own research group, but now it’s totally different. It is a big network of scientists, a huge centre for research. There’s almost no comparison,” says Angela Adamo, associate professor at the Department of Astronomy, referring to the development the department has undergone since she started there in 2006, when she began her doctoral studies about intense star clusters in blue galaxies.

“It is very important to be part of a strong research community, one at the frontline of research. There is a richness to working together that makes us stronger,” she continues.

The change came about because of an investment by the Swedish Research Council in 2008. Stockholm University and KTH Royal Institute of Technology received a ten-year grant to allow them to create the right conditions for interdisciplinary research. This resulted in the Oskar Klein Centre, which now brings together 140 astronomers and physicists so they can better understand some of the universe’s greatest mysteries: What is the nature of dark matter? How do stars and galaxies form and evolve? How do supernovas, neutron stars and black holes behave and function? What is the correct theory of gravity?

Attracted by the promise of interdisciplinarity

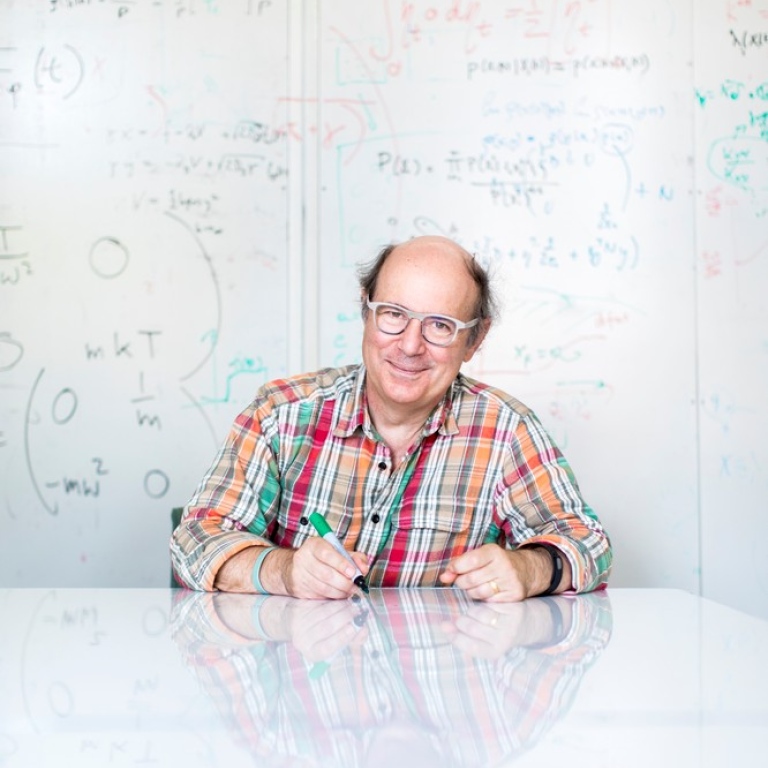

As part of establishing the Oskar Klein Centre, ten new postdoctoral positions were created. One of those employed was Chad Finley, now the centre’s deputy director.

“The way the jobs were advertised made it clear there would be a connection with other researchers. This was one of the things I really missed where I was at the time,” he says.

That was the University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA, home to the IceCube Collaboration’s head office. The collaboration involves researchers from 14 countries who use a unique detector at the South Pole – the IceCube Neutrino Observatory – to capture information from neutrinos as they flow through the universe.

“In Wisconsin, IceCube had a separate building, off campus, and I rarely met researchers from other areas. It was IceCube 24/7. At the Oskar Klein Centre, real efforts are made at multiple levels to get people to interact and engage with each other’s research.”

Ideas are generated by meetings between researchers

Since the centre was founded, one of its aims has been to break down the barriers between different research disciplines. One way researchers do this is by regularly meeting in interdisciplinary working groups built around themes such as Cosmology and Gravitation or Beyond the Standard Model.

“This functions as a type of incubator for new ideas and collaborations. For example, someone who works at CERN, on particle physics, could start collaborating with someone working on the XENON Dark Matter Project,” says Finley.

There are also weekly seminars, often with internationally leading researchers as speakers. Every now and again, people meet up for more informal evening activities and, every year, all the researchers at the centre are invited to the Oskar Klein Days. Doctoral students and postdocs have their own network, through which they help and support each other.

“It formed my research profile. The network is not only about developing the skills to do research, but also the skill of improving the research environment. For example, we talked about how to overcome unconscious biases in research,” says Adamo, who now leads a research group that studies star formation in galaxies and how these processes shape galaxy evolution across cosmic times.

The strategic investment has paid off

Photo: Niklas Björling

Fifteen years after the Oskar Klein Centre was founded, it is clear the investment has paid off. The number of people working at the centre has doubled, and leading international researchers have been attracted here, including Nobel laureate Frank Wilczek and the outstanding theoretical astrophysicist Katherine Freese. In addition, a new campus has grown up around AlbaNova. One of the buildings houses the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics, NORDITA, which gathers leading Nordic theoretical physicists, contributing to the area’s diversity.

For Adamo, returning to Stockholm after a postdoc in Heidelberg was an easy decision. There were two reasons: the Swedish policy on family life and work, which makes it possible to invest in both a research career and in parenting, and the internationally leading research environment offered by the Oskar Klein Centre.

“It is a really great environment to be in. There is a lot of respect for each other and people are really considerate. I got everything I wanted.”

How has the interdisciplinary research environment at the Oskar Klein Centre contributed to your development as a young researcher?

Andrea Gallo Rosso is a postdoc at the Department of Physics and is collaborating within the ALPHA consortium. Their goal is to build a detector with the aim of capturing axions, particles that could comprise the dark matter in the universe:

“In a broad sense, collaborating with people who have different backgrounds is crucial to avoid fossilization and to stimulate healthy research. More practically, my activity wouldn’t be possible without cross-disciplinarity. Building a cutting-edge detector is not a one-person job. It requires the convergence of many branches of physics, and the application of completely different fields of expertise.”

Katherine Dunne is a doctoral student at the Department of Physics and works at the interface between particle physics and the development of instruments used in experimental physics.

“I'm grateful for the OKC’s collaborative and interdisciplinary atmosphere. Aside from my main thesis work in instrumentation and particle physics, I've been able to contribute to an axion experiment, which is outside of my main group’s field. This means I’ve been able to work with theorists and experimentalists with diverse expertise. It has been immensely fulfilling to be able to explore new subjects, and the OKC’s support has been vital in making that possible for me.”

Text: Ann Fernholm

Facts:

Oskar Klein was a Swedish theoretical physicist. He contributed to several ground-breaking discoveries in physics and is renowned for the Kaluza-Klein theory, Klein-Gordon equation, Klein-Nishina formula and the Klein paradox. More on the Oskar Klein Centre

Last updated: January 25, 2023

Source: Communications Office