Thawing permafrost missing from climate negotiations

On 28 February, the IPCC presented a new climate report. But what is required for adaptation measures to be perceived as legitimate and fair? That question is the focus of Lisa Dellmuth's research.

From June 6th to 16th, the UNFCCC secretariat (UN Convention on Climate Change) and Germany hosts the Bonn Climate Change Conference where UNFCCC parties, negotiation groups, researchers and observer organizations from all over the world gather to discuss plans and national commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

At a media event, on Friday 10 June, a group of researchers, with researchers from Stockholm University among them, presented findings on permafrost from the last IPCC report and complemented them with new findings published since the report, further highlighting the urgency to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. At these conferences, science communication often focuses on finding synthesis to give a good overview of different potential outcomes, which can be used to support climate negotiations.

In their presentation, the researchers provided the context and background to a submission to the UNFCCC Global Stocktake on greenhouse gas emissions made by Stockholm University. This submission to the UNFCCC states that permafrost urgently needs to be accounted for as governments measure progress – towards the Paris Agreement goals. Emissions from rapidly-thawing permafrost already are adding as much greenhouse gas emissions as a large top-ten emitting country, such as Japan.

But if continued fossil fuel use causes temperatures to exceed the 1.5°C Paris limit – let alone go higher – these emissions “could become nearly the single largest source of carbon emissions on the planet,” said Gustaf Hugelius, Associate Professor and Co-Director of the Bolin Centre for Climate Research at Stockholm University. “Worse still, these emissions will continue for centuries, meaning we’re placing a terrible burden on future generations to somehow offset the emissions we’re causing to happen today, by our failure to act in time”, he added.

Permanent change on human timescales

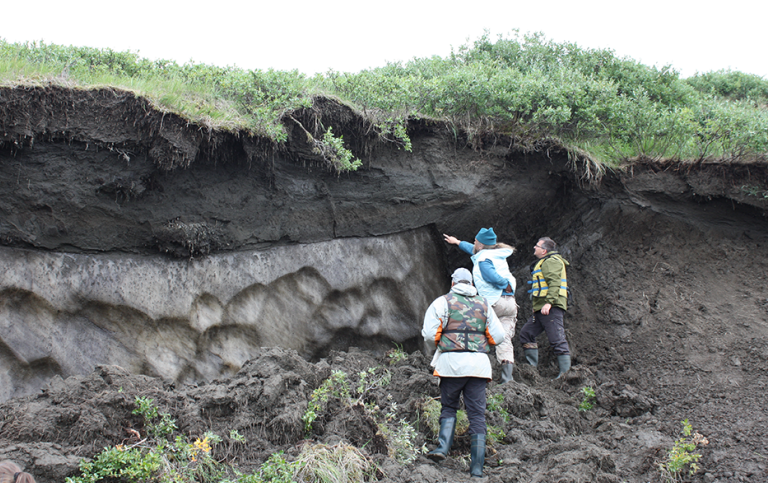

“Right now, at about 1.1°C, we are already committed to losing about 25 percent of surface permafrost,” said Rachael Treharne of the Woodwell Climate Research Center. At current emissions growth, it is likely that near-surface permafrost soils will largely disappear globally, she said. “That’s an essentially permanent change on human timescales – the re-building of new permafrost soils takes thousands of years.”

Stefan Ruchti, a former Swiss climate negotiator now with the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, noted the importance of including permafrost modelling in carbon budgets, to ensure this huge source of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane is included in international climate policy.

Risk for destruction of infrastructure

Thawing permafrost is not only a concerning source of additional CO2 and methane – a great deal of infrastructure, particularly in the Arctic and on the Tibetan Plateau, risks damage and destruction as permafrost foundations thaw, especially affecting Arctic and mountain Indigenous communities. This is not the only disruption these communities face: permafrost thaw also threatens access to traditional food sources, the ability to travel around safely, and the integrity of culturally important sites.

Much of the current interest in permafrost focuses on uncertain and highly speculative events such as a “methane bomb” of sudden emissions release, but the scientific reality is far more pernicious, concluded Hugelius. “Once permafrost thaws, we have no way to stop those emissions,” he said. “The only reliable means to prevent them is to keep temperatures within Paris limits by urgently reducing greenhouse gas emissions – and not in some distant future, but now.”

Greenhouse gas budget for the permafrost region

Many researchers at the Bolin Centre for Climate Research study the link between permafrost and climate in several different ways such as organizing and/or participating in research expeditions to the Arctic to measure fluxes both at land and at sea. “Right now we are also leading the work to compile a new complete greenhouse gas budget for the permafrost region for the period 2000-2020. This new knowledge will feed into the UNFCCC Global Stocktake of emissions,” said Gustaf Hugelius.

UNFCCC – UN Climate Change

The UNFCCC secretariat (UN Climate Change) is the United Nations entity tasked with supporting the global response to the threat of climate change. UNFCCC stands for United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Convention has near universal membership (197 Parties) and is the parent treaty of the 2015 Paris Agreement. The main aim of the Paris Agreement is to keep the global average temperature rise this century as close as possible to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The UNFCCC is also the parent treaty of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. The ultimate objective of all three agreements under the UNFCCC is to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that will prevent dangerous human interference with the climate system, in a time frame which allows ecosystems to adapt naturally and enables sustainable development.

This article was originally published on the Department of Environmental Science

Last updated: October 10, 2022

Source: Bolin Centre for Climate Research