European Commission: Double the herring catches in the Central Baltic

The European Commission proposes to increase the quota for central Baltic herring by more than 100 percent next year. Quotas for sprat, salmon and the collapsed herring stock in the Western Baltic are also proposed to be reduced.

Published: 2024-08-30

As recently as last year, the Commission wanted to stop all targeted herring fishing in the central Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Bothnia. This year's Commission proposal, presented on Monday, shows that the Commission has partly changed its mind about the status of herring in the Baltic Sea

The Commission proposes doubling the quota for the central herring stock from 40,000 tonnes to just over 83,800 tonnes. The sudden change of how much fishing pressure the stock can withstand is based on the latest scientific advice from the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), which indicates that the fishing quotas (TAC) can be increased significantly.

‘However, the Commission has moderated the increase somewhat and wants to see a quota increase of 108 percent instead of the possible increase of 139 percent, totalling 125,000 tonnes, announced by ICES in early June this year,’ says Henrik Svedäng, fisheries scientist at the Baltic Sea Centre.

‘Should be very careful’

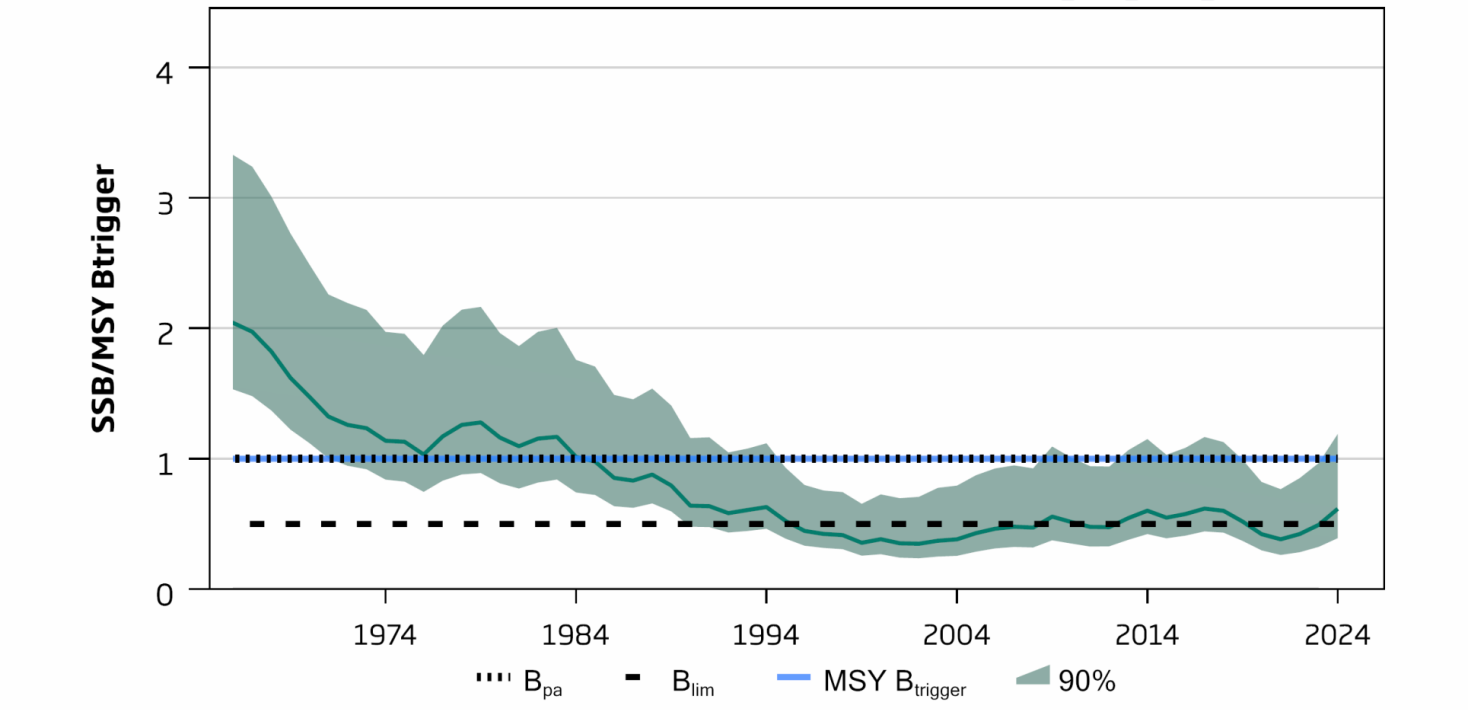

Both ICES and the Commission note that the stock's spawning stock biomass (the biomass of all mature fish) has been below the critical level Blim for most of the last 30 yeare – while this undesirable development has only recently been understood, since the stock was over-estimated for many years. At such low biomass levels, the reproductive capacity of the stock is seriously threatened, and stipulate that fishing pressure must be reduced.

Last year, however, ICES revised its stock assessment models. The new forecasts show signs of better recruitment, and a possible increase to just above Blim. However, the biomass is still well below the Btrigger safety level.

‘If the forecast is correct, it is still only a slight increase, which brings the spawning stock biomass just above the level where the stock is at risk of collapse. Decision-makers should be very careful not to jump the gun and immediately increase the harvest,’ says Sara Söderström, fisheries scientist at the Baltic Sea Centre.

She refers to a recent study in the scientific journal Science, which confirms the dangers of using scientific stock assessments as absolute truths. The study analyses 230 commercial fisheries worldwide and shows that stock assessment models often generate large uncertainties and errors. Overfished and threatened fish stocks are particularly vulnerable to misjudgment and serious overestimations. When scientific stock assessments indicate that such stocks may be recovering, they are often wrong.

Central Baltic herring was overestimated

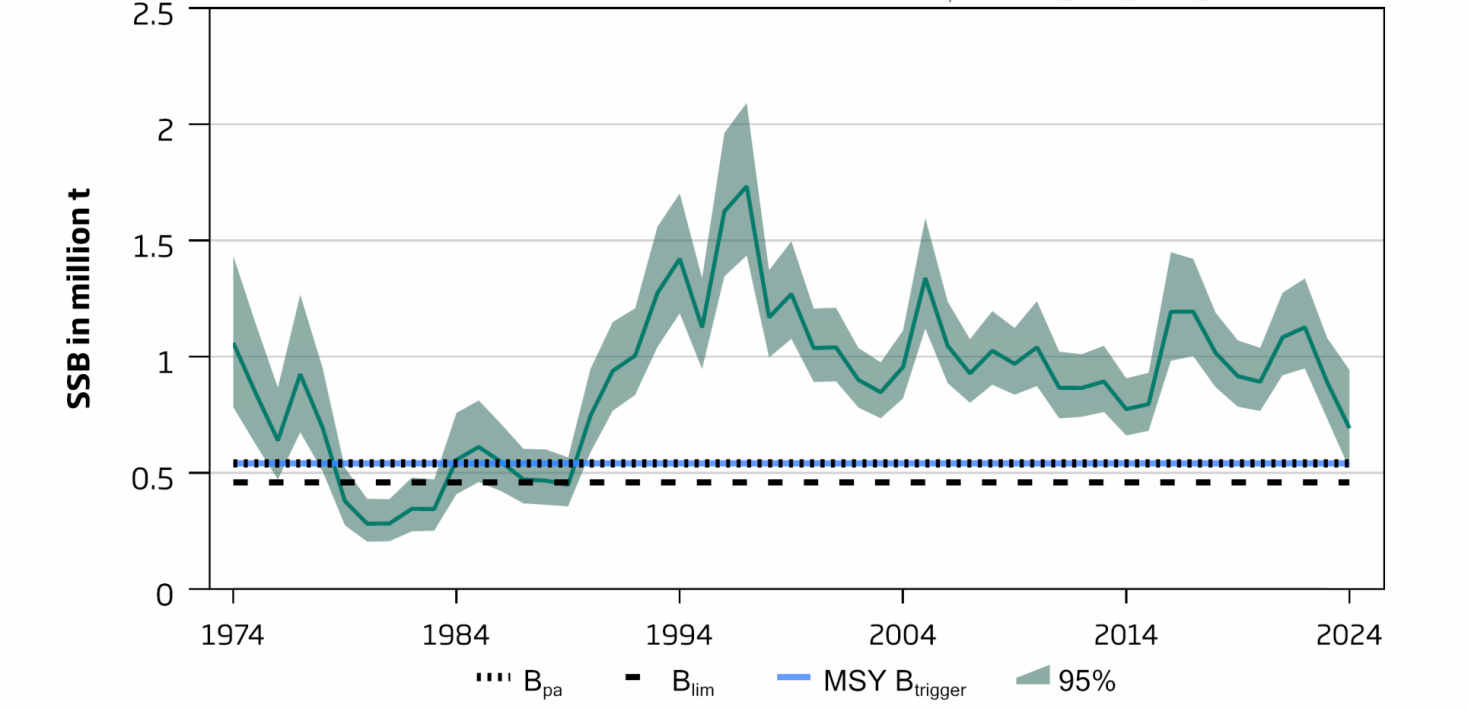

Sara Söderström recalls that the Central Baltic herring stock has previously suffered from just such miscalculations. In the mid-2010s, ICES forecasts showed that spawning biomass increased sharply, to a peak of 1.3 million tonnes. In the following years, estimates improved and by 2021 it was clear that biomass had been greatly overestimated – and fishing mortality clearly underestimated.

The spawning stock biomass had never been close to 1.3 million tonnes, but rather around 500 000 tonnes before declining again.

‘Decision-makers should be much more aware of these large uncertainties, and make sure to not make the same mistake again. At this point, it would be better to wait, decide on more cautious quotas and see how the stock develops,’ says Sara Söderström.

Henrik Svedäng agrees that increased uncertainties and various environmental pressures on marine habitats, such as rising temperatures, cannot be met with increased fishing pressure.

‘It should of course be met with much greater caution. But instead, we are now accelerating at the slightest sign of increased fish production, despite all the clear warning signs,’ he says.

Unclear fate for Gulf of Bothnia herring

The fate of this year's most controversial Baltic fish stock, the Gulf of Bothnia herring, is still unclear. The Commission is still waiting for ICES' delayed stock assessment to be presented in mid-September.

Last year, ICES concluded that the recruitment of the stock was poor and that the spawning biomass was at or below Blim. The Commission therefore proposed to close all targeted fishery, with a by-catch quota of only 1 000 tonnes. The proposal was later rejected by the Council of ministers, who instead set the quota at 55,000 tonnes.

‘Considering how bad things looked for the stock last year – and the fact that the fishing pressure remained far too high – there is a great risk that the situation is just as bad now, or has deteriorated further,’ says Henrik Svedäng.

Sprat stock is declining

For the Baltic sprat stock, the Commission proposes a 42 percent quota cut compared to last year, to a total of 117,000 tonnes.

‘It's good that the quota is being reduced, especially given the uncertainties in the forecasts and the fact that the stock has had such poor recruitment in recent years. The development is very worrying and must be taken into account by our decision-makers,’ says Sara Söderström.

As with the Central Baltic herring stock, ICES forecasts for the sprat stock development are also based on ‘optimistic recruitment estimates’.

The Commission notes that the Fmsy range of possible catch scenarios presented by ICES in its latest advice – from 169,000 tonnes (Fupper) to 130,000 tonnes (Flower) – would put the sprat stock at excessive risk.

According to Article 4(6) of the multiannual management plan for the Baltic Sea (MAP), catch quotas must be set at levels that ensure that the probability of the stock falling below Blim is less than five per cent. Any catch quota within the Fmsy range indicated by ICES would result higher probabilities than five per cent. Therefore, the Commission proposes a quota for sprat around the lowest value of the range (Flower).

Lack of herring affects the ecosystem

For several other commercial stocks in the Baltic, the outlook remains bleak – with the exception of the Gulf of Riga herring, where the quota is proposed to be increased by 10 per cent.

• The herring stock in the western Baltic Sea is collapsed (since several years ago) and can only be caught as by-catch in other fisheries. The Commission proposes to halve the by-catch quota to 394 tonnes.

• The two cod stocks in the Baltic Sea show no signs of recovery despite years of fisheries regulation. Cod is still caught as by-catch in flatfish fisheries. The Commission is proposing to reduce by-catch quotas for these stocks as well.

‘Whatever the case, most of the Baltic fish stocks are at low levels. Low fish biomasses have a negative impact on ecosystem functions, such as nutrient cycling and the role of the sea as a carbon sink and habitat for many other fish, birds and mammals. Excessive exploitation of so-called forage fish, such as herring and sprat, creates poor conditions for other species higher up in the food chain,’ says Henrik Svedäng.

Important to protect herring sub-stocks

The reasons for the Commission choosing to propose a quota for central herring at the lower end of the Fmsy range set by ICES are said to be the scientific uncertainties and optimistic forecasts for the stock's recruitment, coupled with the fact that there is more than a 50 per cent risk that the spawning stock biomass will not grow above the Btrigger safety level in the coming years – even if the stock is not fished at all.

‘Another important factor to be aware of is that the ICES estimates do not take into account that herring is a so-called population-rich species. This means that the total stock is made up of a number of different sub-stocks that have different adaptations and behaviours. These sub-stocks are of varying sizes, and constitute the stock's production units. If they disappear, both the genetic diversity and the stock's ability to regain its former stock size disappear,’ says Henrik Svedäng.

‘Hopefully, the EU fisheries ministers will take this into account when they decide on the final quotas later this year,’ he says.

Next year's fishing quotas in the Baltic Sea will be decided at the Council of Ministers meeting on 21-22 October.

Text: Henrik Hamrén

Last updated: August 30, 2024

Source: Baltic Sea Centre