New study: Sharp decline in adult eel in the Baltic Sea – fishing mortality has been underestimated

The migration of adult eels from northern European seas is continuing to decline. This is revealed by a new study based on international, fishery-independent trawl surveys. The results also suggest that the level of fishing mortality for eels in Swedish coastal waters has been significantly underestimated. "The situation for eels is very critical, and it is unreasonable to consider the impact of Baltic coastal fishing to be minor," says the article's author, Henrik Svedäng.

Published 2025-09-01.

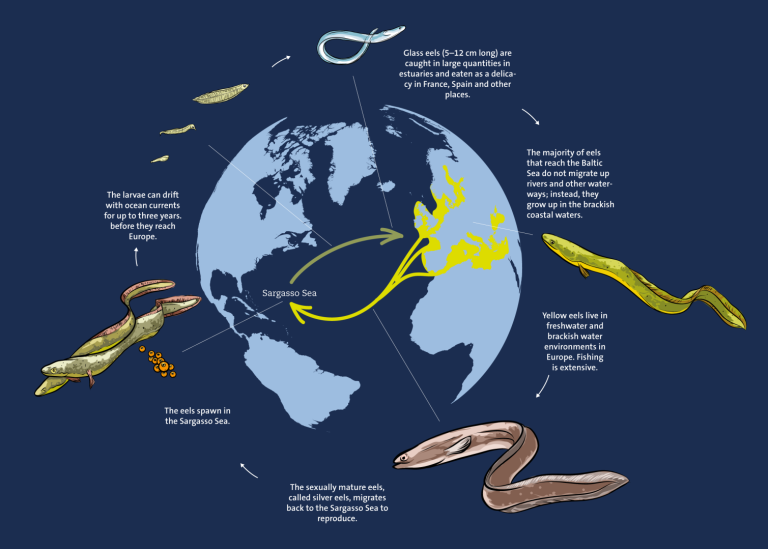

Fifty years ago, Swedish fish researcher Gunnar Svärdson raised concerns about a worrying trend for European eels (Anguilla anguilla) in Sweden. The number of eel fry and yellow eels migrating up Swedish waterways had declined sharply, as had the number of nearly sexually mature silver eels leaving the Baltic Sea. A dramatic decline in eel stocks was later noted in other European countries too, and today the European eel is classified as critically endangered on both the Swedish Red List and by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

In order to reverse this negative trend, EU member states were tasked in 2007 with developing national eel management plans, with the aim of increasing the migration of adult eels. Although the sharp decline in glass eels reaching European coasts is well documented (in the North Sea area, there has been a decline of more than 99 percent since the 1980s), it has been considered more difficult to track the development of migrating adult eels, as sea migration occurs over a longer period of the year from many different environments.

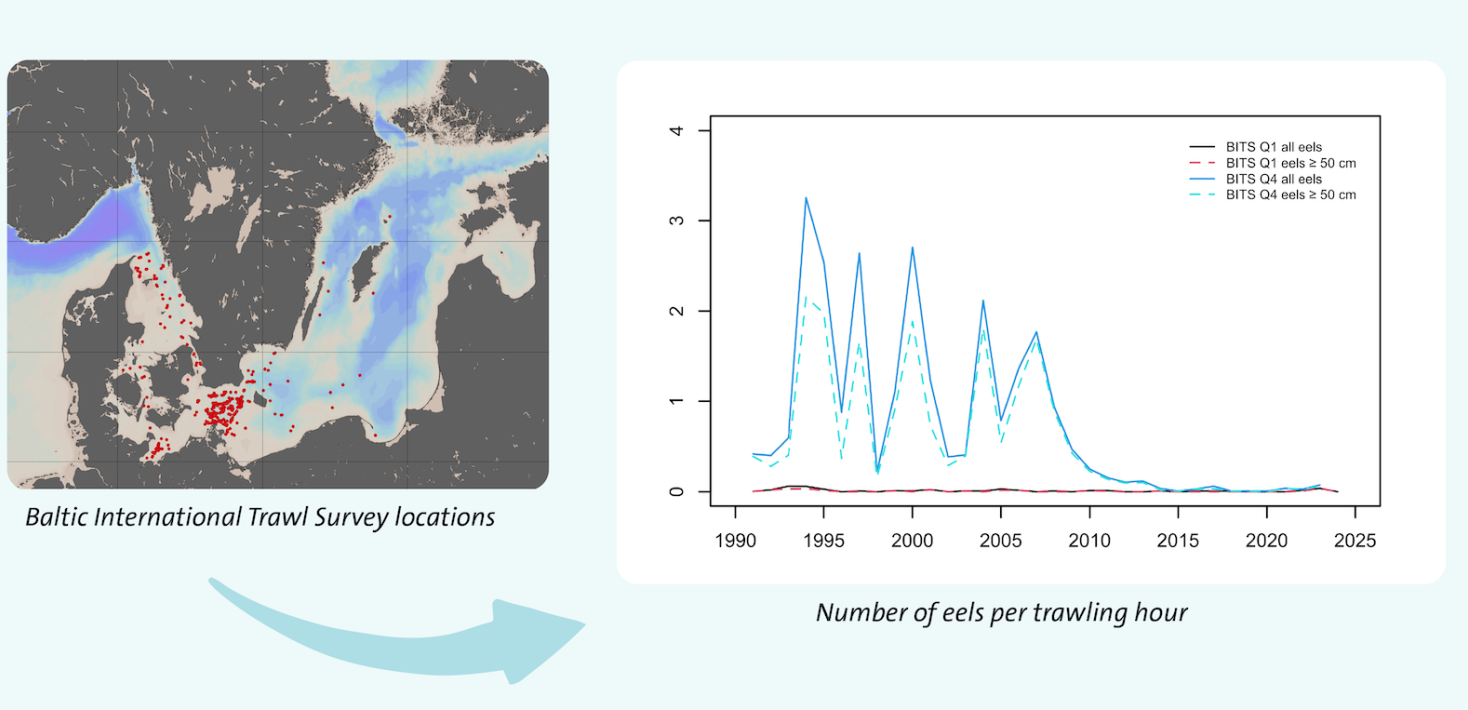

In a new study, fisheries researcher Henrik Svedäng has adopted a new method for monitoring the development of the adult eel population, namely analysis of the annual bottom trawl surveys conducted by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES). These sampling programs, known as surveys, are designed to track developments of marine species, but several of them include catches of eel on such a scale that it is possible to study changes over time.

The study showed that the abundance of large eels (more than or equal to 50 centimetres) has declined significantly in recent decades, both in the Baltic Sea and in the North Sea, including the Skagerrak and Kattegat.

“This shows that the protection of eels has not been effective. On the contrary, the decline has accelerated since the eel management plans were developed, which indicates a collective failure within the EU, including the UK,” says Henrik Svedäng.

Swedish eel management

The current Swedish eel management plan was developed in 2008 and is based on four types of actions: Measures aimed at reduction of the fishery, Measures to improve possibilities for downstream migration, Restocking of glass eels and elvers and Control measures.

To reduce the impact of fishing, the fishery on the west coast was completely closed in 2012. In inland waters and on the east coast, fishing was permitted for licence holders, with the intention of phasing it out in the long term since no new licences were being granted.

This fishing ban on fishing on the west coast has been described as the most important and effective measure implemented in Sweden, in the evaluation of the Swedish eel management plan completed by research council Formas earlier this year. Henrik Svedäng agrees.

“The coastal test fishing conducted by the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) on the west coast since 2012 shows an increasing trend for larger yellow eels,” he notes.

On the east coast, where fishing has been allowed to continue, no corresponding targeted test fishing is carried out. Instead, knowledge about the development of the stock is gained by catching and tagging eels, which are then released again. When a fisherman catches a tagged eel, it is hopefully reported, and the ratio between tagged and untagged eels in the catches is then used as a basis for the assessment of the size of the stock in Swedish waters and the impact of fishing on it.

Between 2020 and 2024, 12 such tagging experiments were carried out, and during the same period, the average recapture rate was 1.1 per cent in Swedish eel fishing and a further 0.5 per cent in Danish eel fishing. From this, analysts at SLU estimate the fishing mortality rate on the Baltic Sea coast to be 0.003. Although the method is admitted to be uncertain, the analysis is described as indicating a positive trend for the status of silver eel along the Swedish Baltic Sea coast, and reflecting a sharp reduction in fishing pressure.

“These figures for fishing mortality are completely unreasonable. If the impact of fishing were so small, the amount of eel in Swedish waters would amount to many thousands of tonnes. Eel would then be one of the most common fish in the Baltic Sea, and it is quite clear that this is not the case," says Henrik Svedäng.

“Another interpretation of the data is that the method no longer works, and if it is to be used, it needs to be tested against fisheries-independent data.”

Declining catches – declining stocks?

Reported catches of eel on the Swedish east coast have declined steadily in recent decades, from 400 tonnes in 2007 to less than 100 tonnes in 2019–2023. This can also be seen as a sign that the restrictions introduced have had an effect. For example, in its proposal for a new eel management plan, Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management writes that the impact of Swedish fishing in the Baltic Sea has declined rapidly over time “as a result of the restrictions introduced since 2007”.

However, Henrik Svedäng suggests that there is a more likely explanation behind the declining catches.

“It is probably simply a result of there being fewer eels to catch. The sharp decline in eel fry recruitment has impacted all stages of their life cycle. The decline in catches coincides with the decline in the abundance of larger eels observed in trawl surveys of this area,” he says.

New management plan in development

In June, the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management presented a proposal for a revised national eel management plan for 2025–2030, which has been out for consultation. In addition to achieving the long-term (125-year) goal of the EU Eel Regulation that the number of migrating silver eels should be 40 per cent of what it would have been without human impact, the plan sets interim targets, such as that human-caused mortality in Swedish waters should not exceed 25 per cent by 2050.

The new plan no longer includes the restocking measures previously strongly criticised by the Baltic Sea Centre. However, there are also no new restrictions on fishing (for example, the proposal by Formas' investigators to reduce the permitted catch from the current 8 tonnes per fisherman to 1 tonne is not included), despite the fact that ICES has become even more explicit in its advice that no catches of eel should be allowed at any stage of life. Instead, the impact of Swedish fishing will only be reduced by licence holders eventually stopping fishing.

“The situation for the eel is critical. In addition to the fact that the population itself has been decimated, another complicating factor is that sex determination in eels is unstable – if there are few individuals in the same place, very few of them develop into males. This means that there is a risk of extinction even if a certain number of females remain. Waiting for the fishermen to cease fishing, for instance, by getting too old for fishing, will take too long,” says Henrik Svedäng, adding:

“Since fishing on the east coast takes place along the eel's migration route from north to south, reduced fishing due to the disappearance of gear will increase the likelihood that more eels will be caught by remaining gear further along the migration route.”

“Every living eel should be considered important”

The Baltic Sea Centre has responded to the consultation on the proposed new eel management plan, emphasising, among other things, that closures of fishing are crucial for the development of the current stock. “If we want to save the eel, we must stop fishing for eel in the sea, where most naturally migrated eels are found and where there is the greatest potential for measures to have a positive, immediate effect,” they write, among other things. The revision of the plan is to be completed by 1 October.

“Every eel alive today should be considered important until a recovery of the adult population can be confirmed. The positive trend for the local yellow eel population on the west coast since the ban in 2012 shows what the eel’s continued survival depends on,” says Henrik Svedäng.

Text: Lisa Bergqvist

Read the article in Frontiers in Fish Science:

Last updated: September 3, 2025

Source: Baltic Sea Centre