PFAS back to haunt us – through sea spray

The man-made, and in many cases hazardous, chemicals called PFAS were previously believed to finally be transported to and diluted in the oceans. But at the last Baltic Breakfast, scientists at Stockholm University presented new research showing that these chemicals are enriched at the sea surface and return to land through sea spray aerosols, creating an almost never-ending transportation cycle.

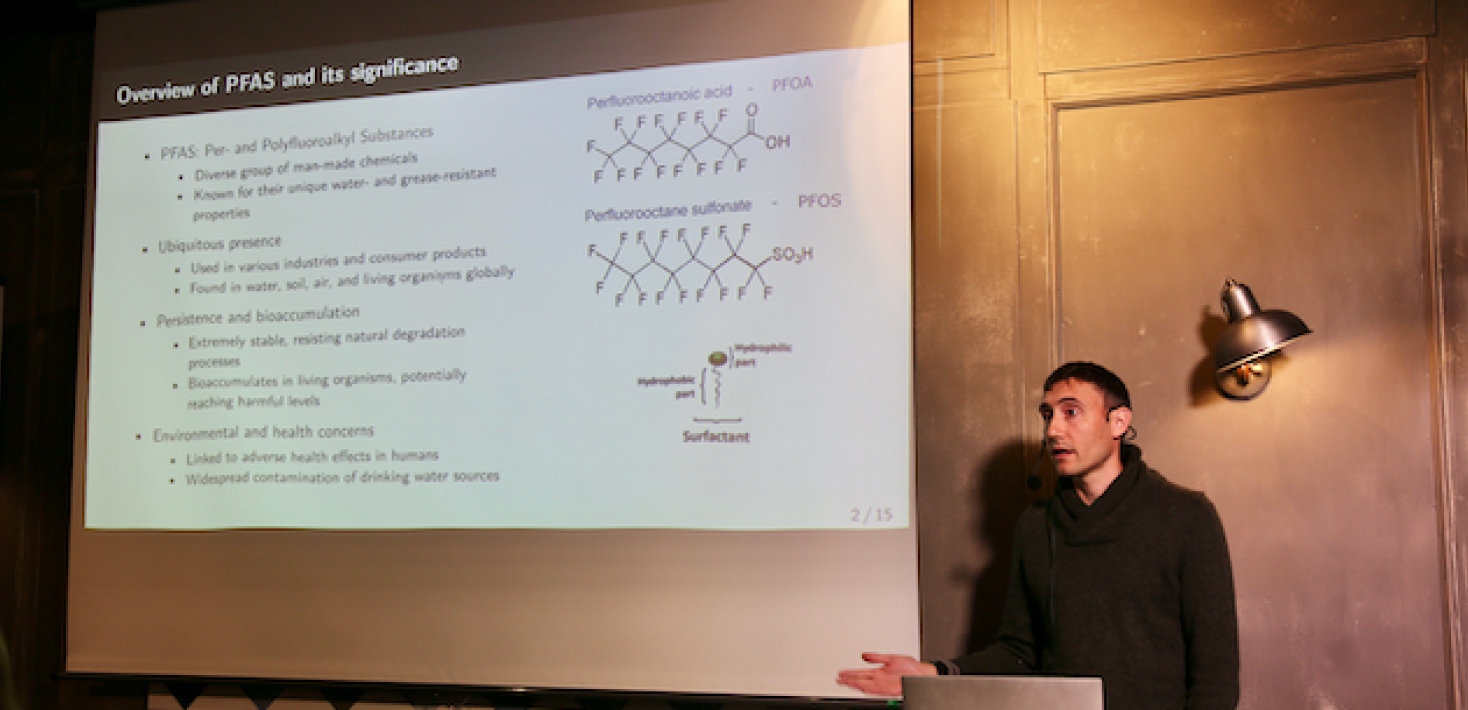

PFAS – Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances – is an extremely large group of man-made chemicals containing fluorine and carbon atoms that bind together multiple times. The substances are known for their water and grease resistant properties and are used in various industries and consumer products. They also have in common that they are extremely stable and don’t degrade in the environment. In many cases they are bioaccumulating, meaning they are stored and concentrated in living organisms.

“They are essentially everywhere”, says Matt Salter, scientist at the Department of Environmental Science, Stockholm University. “They will be in this room in numerous forms.”

Some PFAS have been proven harmful for both the environment and for humans, and most use of the substances PFOA and PFOS have already been banned, unfortunately to be replaced with other similar PFAS in many cases.

Many different pathways

PFAS reach the environment in many different ways; in form of air emissions from production, during use and disposal of consumer products such as waterproof textiles and stain-resistant coatings, and through landfill leachate and wastewater. Another major source is the use of PFAS in firefighting foam, which has caused contamination of land and drinking water.

A more recently discovered pathway for PFAS to reach the atmosphere is through sea spray aerosols. Sea spray aerosols are small particles of seawater generated by bursting bubbles after wave breaking. As PFAS are surfactants, that accumulate at the surface of bubbles, PFAS-enriched droplets are ejected into the atmosphere when the bubbles burst.

As the oceans cover about 70 percent of the planet, the researchers suspected this to be a big source of aerosols to the atmosphere. To investigate the phenomenon, Matt Salter and his colleagues performed laboratory experiments with bubbling water in closed tanks. The experiment showed that PFAS were extremely enriched in the aerosols that were formed.

“This is a really an efficient process of transporting PFAS from a water body, in this case the sea water, to the atmosphere above”, says Matt Salter.

Investigations in the field confirmed the picture. Correlations between PFAS and sodium, common ingredient in sea spray aerosols and therefore used as a tracer, at the remote site Andoya in Northern Norway, indicated that sea spray aerosols really are an important source of PFAS to the atmosphere.

“Previously, the thinking was more that these PFAS are transported to the ocean and that is the ultimate sink; they will sink to the bottom and get into the sediment and stay there”, explains Matt Salter. “That surely happen to a certain extent, but what we see here is that some of these PFAS accumulate at the surface, get ejected and potentially come back and re-contaminate terrestrial environments.”

High levels in sea foam

Professor Ian Cousins, Department of Environmental Science at Stockholm University, has focused a lot on PFAS in his research, and could present more evidence for the sea being a source back to land for PFAS.

Extremely high level of PFAS have been found in sea foam. Along the Danish west coast, concentrations as high as 1 700 000 ng/L has been detected for four types of PFAS in sea foam. This can be compared to the underlying seawater in which the level was 9 ng/L and the Swedish drinking water guideline of 4 ng/L.

“This foam is just a lot of bubbles so you will get enrichment on the bubble film”, explains Ian Cousins. “Stable foams form when there are enough surfactants present in the water, but there are many other surfactants than PFAS; natural as well as man-made”.

Concern has been expressed for the effect of the high PFAS levels on for example surfers and near-shore grazing animals. However, for transportation, the sea spray aerosols are more important, as the foam itself is quite heavy and won’t travel very far. That sea spray aerosol travel inland is well-known and the reason that sea salt is affecting constructions is coastal areas.

“You can expect as you go inland, a drop-off in the PFAS levels”, says Ian Cousins. “You have a lot of mass deposited quite quickly the first few hundred meters, and then you have less and less deposited from the smaller particles further inland.”

Modelling to predict importance

To predict how important the sea spray process is globally, and compared to other sources, Ian Cousins and his colleagues has used modelling tools. The results showed that for PFOA the sea is now comparable to other sources. In case of PFOS, sea spray aerosols is now by far the dominant source of the chemical to the atmosphere.

“It’s like a continuous circle of PFAS”, says Ian Cousins.

The modelling also showed that the northern hemisphere is expected to be more impacted than the southern hemisphere. Coastal areas, such as the UK and the west coast of Sweden, Norway and Denmark are expectedly among the most impacted.

Further proof of the importance of sea spray aerosols have been found in the field; in Denmark, high levels of PFAS have been detected in groundwater in coastal areas that lack proximity to other sources. Yet unpublished studies have also shown exponential trend in the PFAS concentration going inland from the west Danish coast.

“There are multiple lines of evidence now that the sea is a secondary source of PFAS to land, says Ian Cousins. “These PFAS are going to continue to cycle. All we can do is to wait for these legacy PFAS to slowly dilute into the deep oceans.”

“Don’t go away”

A possible implication of the sea spray transportation of PFAS is contamination of coastal sources of drinking water, which can result in high clean-up costs. Coastal farming might also need to be moved.

“You should avoid the contaminated sea foams”, says Ian Cousins. “I wouldn’t even want to touch them – they are extremely contaminated. This is another lesson we have to learn about these persistent synthetic chemicals: we can find surprisingly processes later, that can cause us enormous problems. Because these chemicals don't go away.”

In the European union five countries have proposed a restriction of all PFAS as a group and the discussion is ongoing about the proposal.

“This is great, but its only happening in Europe. It should be expanded globally”, says Ian Cousins.

Matt Salter points out that the process of sea spray as a route for chemicals could be relevant not only for PFAS but also for other surface-active pollutants.

“I’m sure that 20-25 years ago when PFAS was emitted, no one thought about this as being a route, and there are things that we haven’t thought of now. These things will come back to haunt you if you don’t handle them correctly.”

Text and photo: Lisa Bergqvist

See a recording of the seminar:

Last updated: October 4, 2023

Source: Baltic Sea Centre