New study shows: No significant risk to humans or animals from aluminium treatment

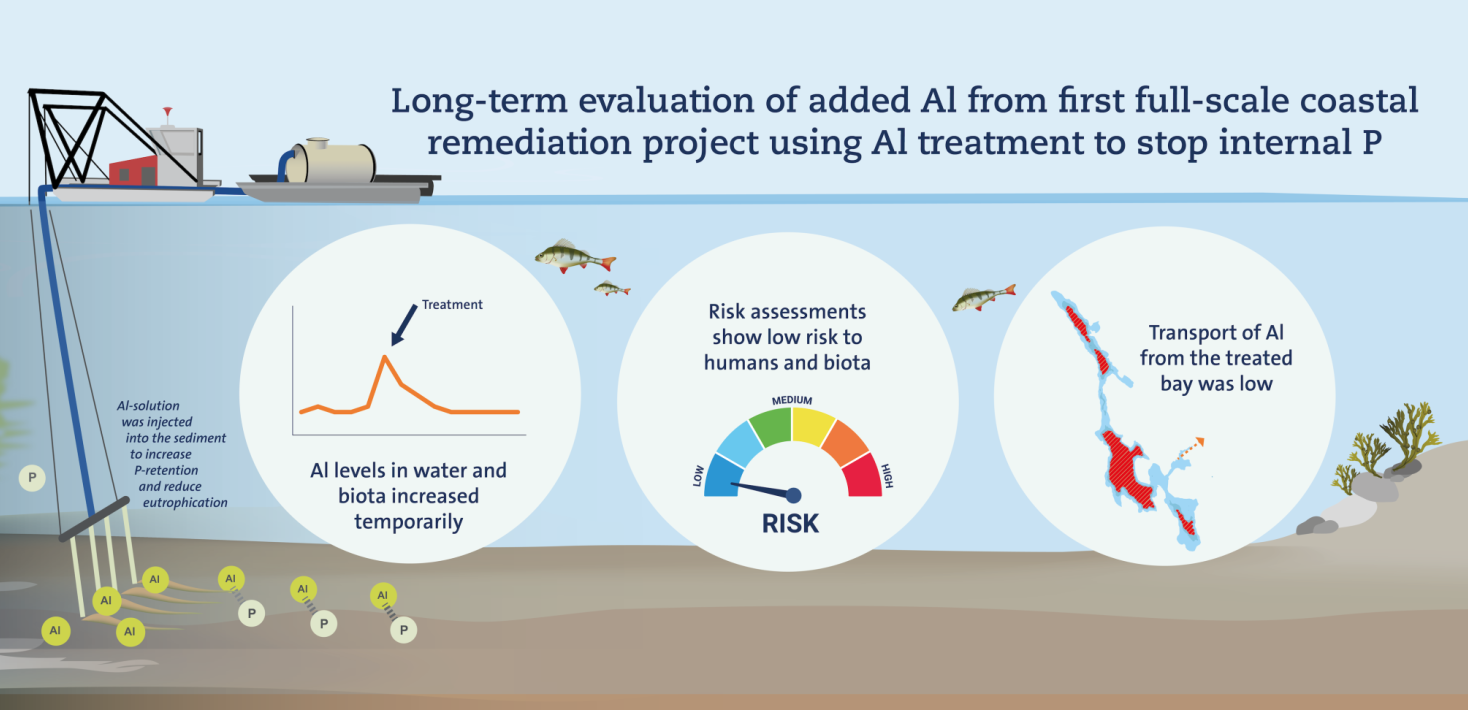

The aluminium treatment of the previously eutrophic bay Björnöfjärden posed no significant risk to humans, animals or vegetation, a new study shows. Aluminium levels increased in the water, fish and algae after the treatment, but only temporarily, and the transport of aluminium to nearby areas was low.

Using aluminium to bind phosphorus in sediments is a well-tested method of reducing eutrophication in lakes with high levels of stored nutrients. During eight summer weeks in 2012-2013, the method was tested for the first time on a large scale in a eutrophic bay - Björnöfjärden in the Stockholm archipelago - as part of the Living Coast demonstration project.

The treatment had a rapid effect on phosphorus concentrations in the water and improved the environment in the bay. Now the researchers have investigated how aluminium levels in the water, fish and algae changed during and after the treatment, and what risks this posed to humans and biota. The analysis includes 10 years of data from Björnöfjärden and a control bay.

The results show that the aluminium concentration in the surface water increased by 50 per cent after the treatment. The following year, however, the concentration decreased to the same level as before the treatment.

“The aluminium was applied directly into the bottom sediment to bind the dissolved phosphorus there. But the dose was adjusted to also bind the phosphorus to be released in the coming years”, explains Emil Rydin, researcher at the Stockholm University Baltic Sea Centre and one of the authors of the study.

The researchers also looked at how much aluminium was transported from Björnöfjärden to the neighbouring Nämdöfjärden. In 2013, the transport was estimated at 1 tonne, which is about 3 per cent of the supplied aluminium.

"The fact that the transport was so low and that the concentration in the water fell rapidly shows that the method of adding aluminium directly to the bottom sediments was effective," says Emil Rydin. "The aluminium stayed in the sediments and bound phosphorus, as intended.”

Aluminium levels were also measured in samples of bladderwrack and perch from the bay. The measurements showed no clear pattern in the musculature of the perch. However, in the liver and gills of the fish, there was a clear increase in aluminium after the treatment, but this quickly returned to the original level. No measurements were taken of bladderwrack before the treatment, but after the treatment the levels in Björnöfjärden were higher than in the control bay. A few years later, concentrations had fallen to the same level as in several other similar bays, while concentrations in the control bay remained slightly lower.

There has sometimes been concern that aluminium treatment in lakes and seas may be harmful to aquatic organisms. This is partly because aluminium released from the soil during acidification has been shown to damage fish gills, among other things. However, the new study shows that the risk of impact on bladderwrack or perch in Björnöfjärden was very low.

"Björnöfjärden is not acidified - the pH is stable between 6 and 8 - and there are also relatively high levels of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and other substances that reduce toxicity," says researcher Linda Kumblad, another author of the study. "For aluminium to pose a risk under these conditions, the concentration would have to be many times higher than what was measured in Björnöfjärden during the Al-treatment."

According to a/the risk assessment the aluminium levels also posed no significant risk to people who ate fish from Björnöfjärden or drank desalinated water from there.

"Even in the period immediately after the treatment, aluminium levels were 17 times lower than would be risky for human consumption," says Linda Kumblad. "For example, bread or cereals normally contain much higher levels of aluminium than the fish in Björnöfjärden.

Overall, the Björnöfjärden project shows that aluminium treatment can be an effective tool for reducing eutrophication, even in coastal areas, say the researchers.

"In such bays, where there is a lot of nutrient cycling even though the external input from land has been reduced, active restoration measures may be needed to reduce eutrophication," says Linda Kumblad. "This study shows that the aluminium treatment of Björnöfjärden was successful in reducing phosphorus levels and posed no risk to humans or aquatic organisms."

Text: Lisa Bergqvist

Read the full study in Water Research:

Long-term evaluation of potential Al toxicity after an Al treatment in a coastal bay

Last updated: September 11, 2024

Source: Baltic Sea Centre